by Susan Taylor Block

(Click on photos to magnify them. Double-click and scroll to see more.)

This aerial photo, taken about 1930, includes images of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad complex (far left), including Union Station, the building with a rounded corner. Here, St. John’s Episcopal Church still stands on North Third Street, and many handsome houses grace the north side. Warehouses and other spaces of maritime business line Water Street, and the Colonial Apartments building and Y.M.C.A. stand, just left of St. James Episcopal Church. (917)

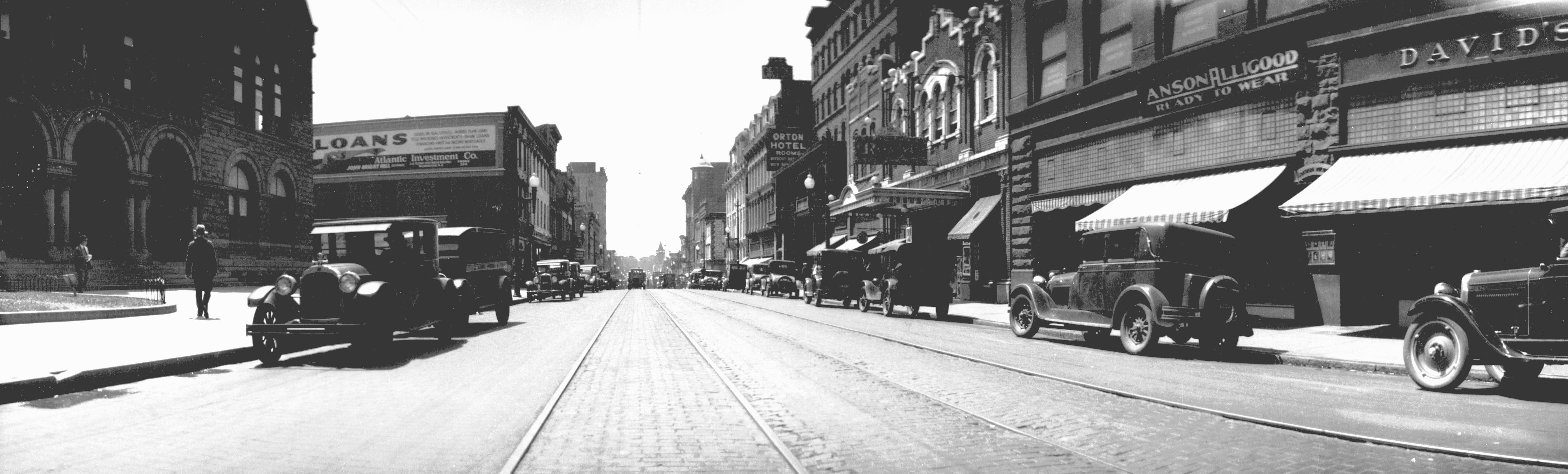

The subject of this photograph is a Decoration Day parade, but the architecture also is fascinating. The Romanesque-style U. S. Post Office building on the right was constructed from 1889-1891. Designed by the supervising architect for the U. S. Treasury, W. A. Freret, it featured brownstone hewn from a quarry in Wadesboro, NC. Interior decorations included fine lighting fixtures from Philadelphia and massive cherry roll-top desks made in Baltimore. Sadly, the building was razed in 1936 for the dual purpose of constructing a larger post office and creating jobs for some of the many Wilmingtonians the Depression had idled.

The three-story building just beyond the post office, long-known as the Acme Building, and two buildings to the north, replaced the handsome Platt Dickinson House and adjoining garden. Dickinson’s wife, Alice, raised her nephew, Pembroke Jones, there. The alleys, east and north of the property still bear their original names: Dickinson and Vance, the maiden name of Dickinson’s first wife. The balustrade on the left is the edge of The Orton hotel, located at 115 North Front Street. Built in 1886 by Col. Kenneth M. Murchison, the hotel was named for the plantation he owned in Brunswick County. About 1888, art collector and Atlantic Coast Line president Henry Walters purchased an interest in The Orton, adding to its gilt. The opulent inn played host to many famous folks through its early years, including Thomas Edison. By the time Mr. Moore took this photo, the hotel’s sparkle was nearly gone. Some rooms were being leased as apartments, the most famous tenant being artist Elizabeth Chant who complained of hearing gunfire within the building. The Orton burned in 1949. (138)

Looking south from the intersection of Front and Chestnut streets, the spire of City Market is visible (center) and streetcar tracks dissect the brick pavement. The Royal theater (on right), with its distinctive parapet, was built by J. H. “Foxy” Howard and Percy Wells, owners of the Bijou. They sold the Royal to George Bailey in 1924. Although The Bijou had more character, The Royal was considered the “most fashionable theater” in Wilmington in the late 1920s and, according to the Morning Star, had “a clientele that is not surpassed by any picture house in the state.”

The movies were not the only attractions. Will Rehder Florist, located next door, furnished palms and potted flowers for the lobby, as well as fresh flowers for a large box on stage. The Royal featured a orchestra and an organ. Crimson velvet draperies unveiled every movie and an organ and pitted orchestra provided soundtracks. After dark, electric lights made the little rabbits that bordered the Royal marquee go “round and round.” The Royal also doubled as a house of worship from 1926 to1928, when First Presbyterian Church members met there, at times, while their new building was under construction. Church of the Covenant and St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church convened there also for Sunday night services. (43)

On January 10, 1925, the Hotel Cape Fear (on right) opened to the public; it marks the former site of Louis T. Moore’s family home. The hotel, designed by G. Lloyd Preacher and Company, cost $850,000 to build. That was a boom time for large hotels: the Ocean Forest in Myrtle Beach and the Grove Park Inn, in Asheville, also were products of this era. By 1933, close to 3000 people a month dined at the Hotel Cape Fear Coffee Shop. During months ending in an “r,” New River oysters, harvested at Snead’s Ferry, were the house specialty. No doubt they were on the menu on March 3, 1933, when Wilmington’s own Franklin D. Roosevelt Inaugural Ball was held at Hotel Cape Fear. Loop McGowan and the Loop Boys provided the music. Weather measuring instruments that sit atop the old U. S. Post Office (left) comprised the entire weather bureau in those days. The rear of the Post Office property was known as Post Office Park. It was a good place for staging small fairs and exhibits, and its benches were popular with people watchers. (172)

The corner of Front and Chestnut streets was considered the busiest, windiest intersection in town. Murchison National Bank first occupied the 1902 Acme Building (on right), designed by Charles McMillen. The thriving bank was founded by the same man who built The Orton hotel, Kenneth M. Murchison. In 1914, Murchison Bank moved across the street to the eleven-story Murchison Building seen on the left. The Bijou (four doors down on the left, with pointed roof), North Carolina’s first movie theater, opened December 24, 1906 in a tent. The earliest features were fifteen minutes long, and ran over and over, all day long, for three days.

The Bijou building pictured here was constructed in 1910. By 1924, it was the only playhouse in the country specializing in short-length “moving pictures.” In the twenties, high school students called the Bijou the “Goobie Show,” a reference to the theater’s favored snack. Patrons ate peanuts, heated in a freestanding roaster, filling the room with aroma and the floors with shells. According to Rosalie Oliver, Louis T. Moore usually sat in the rear of the movie theater during daytime showings, using any light that filtered in to read the newspaper. The Bijou was convenient: Mr. Moore’s Chamber of Commerce office was located at the rear of the Acme Building.(950)

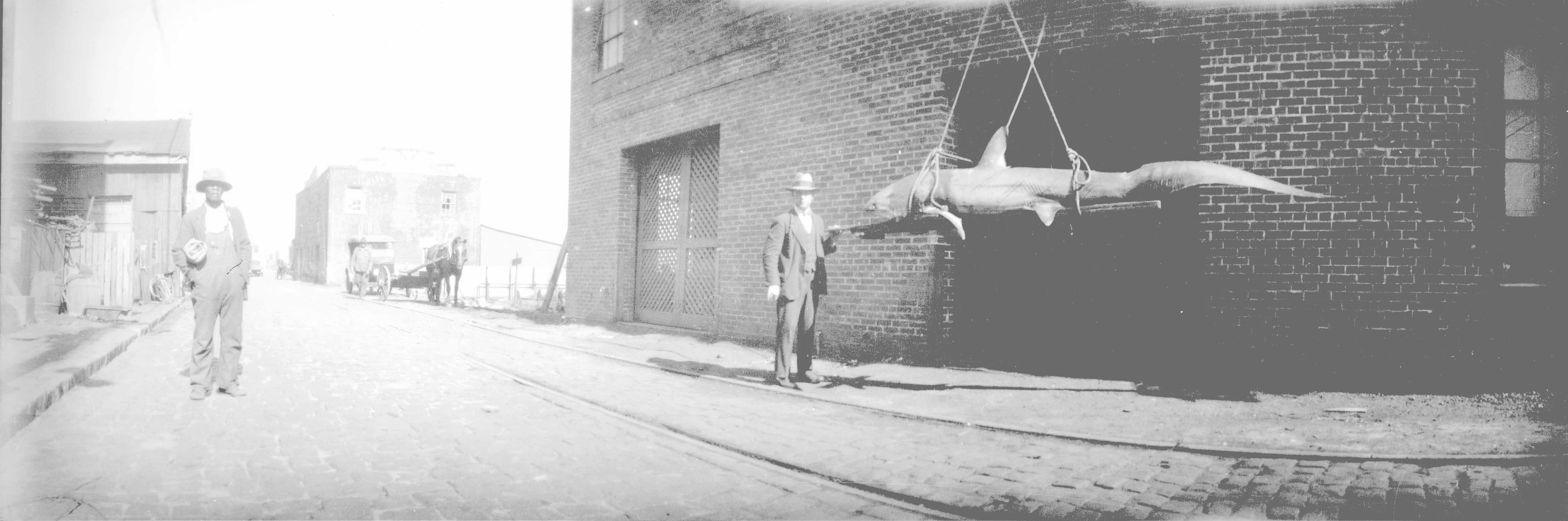

Adding an earthy element, seafood markets thrived in downtown Wilmington from colonial days throughout Louis T. Moore’s days as photographer of panoramics. In June 1932, seven firemen from Wilmington and Hiram Hewlett, the night patrolman at Wrightsville Beach, caught a nine-foot shark. They were fishing at The Rocks, aboard Captain Fred Hanson’s 40-foot boat, the Newport. Hewlett, seated on the side of the boat, with his feet dangling in the water, “narrowly escaped having his foot bitten off.” Here, an unidentified man poses with the shark, at 116 South Water Street: J. B. Fales Fish House.

“Fales Fish House had competition, but they were the best,” said Clarence Jones, who made frequent trips to downtown Wilmington. “Whenever someone caught an unusual fish, they would display it out front. It didn’t matter if the shark or dolphin stayed out too long, because, in those days, no one ate shark or dolphin. Fales would take care of destroying the fish when the time came.

“A lot of people from the country took catfish to Fales Fish House. Almost everybody could catch a catfish and they live in just about every creek. There would be big “catfish skinnings” and the man in charge could make just a little incision in each fish and then pull the whole skin off, all at one time. Then Mr. Fales would buy all the catfish and resell them.” (207)

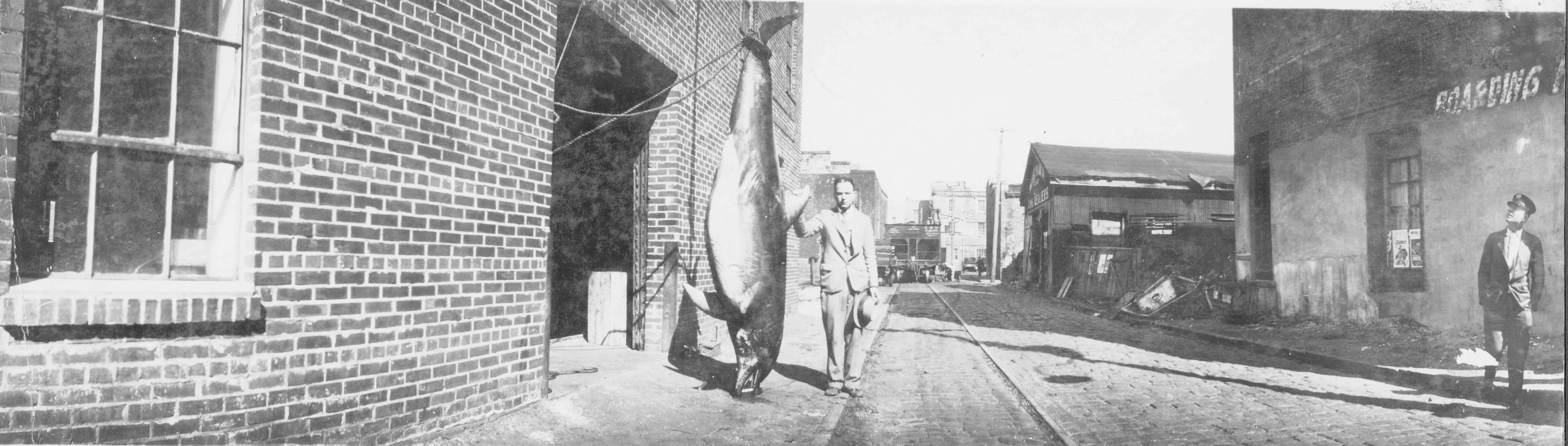

Captain Will Moore carried a harpoon on his fishing boat, Tanager for years, just itching to spear a porpoise. Finally, on June 23, 1932, a 300-pound dolphin crossed his watery path, near The Rocks. After Captain Moore harpooned the dolphin, it swam 200 feet before being checked by the half-inch line. Members of the fishing party, including George Clark, were “compelled to battle with the porpoise for four hours before landing him.” After showing off the fish at Wrightsville Beach, they took it to J. B. Fales Fish House. Here, Albert Franklin Fales, brother of Wilmington historian Robert M. Fales, M. D., poses with the sagging catch. (203)

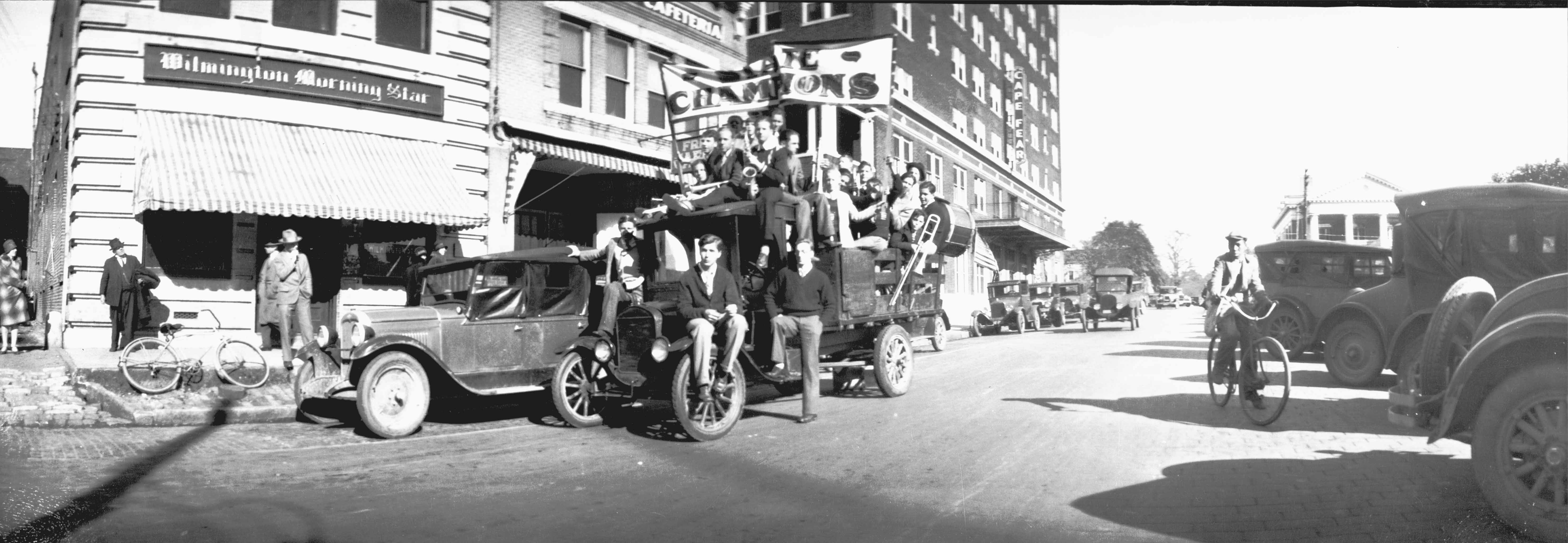

The Morning Star occupied the two-story building at 109 Chestnut Street. In 1929, Wilmington had two newspapers: the Morning Star and the News Dispatch. The News Dispatch, owned principally by Wilmingtonians Chesley C. Bellamy, Joseph E. Thompson and Joshua Horne, was an afternoon paper. The Morning Star, established in 1867, was one of four newspapers owned by Page Brothers of Columbus, Georgia. Rinaldo Page was Wimington manager and Lamont Smith, editor.

Josephus Daniels, editor and publisher of the News and Observer and Secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson, was a great admirer of one of the Morning Star’s finest editors. “My favorite among the state dailies in the early 1880s,” wrote Daniels of his youth, “was the Wilmington Star, edited by classical scholar Theodore B. Kingsbury. I devoured his editorials and his reviews of books in fine literary style.” The Star, always the favored paper in Wilmington, had the same ranking throughout much of eastern North Carolina. One verbose Wilson resident who spouted his opinions to anyone who would listen, irked a fellow businessman one time too many. “I always know what you think on any subject before you have opened your mouth,” the angry man cried. “You read the Star one day and the next day spout what it says.”

During the 1920s and ’30s, Post Office Park was a popular gathering spot for sports broadcasts. With television decades away, the Star News rigged up a primitive instant replay system in front of their building. World Series games were reproduced on a magnetic playing board. Newspaper employees translated Associated Press telegraph transmissions into play-by-play reenactments by positioning characters on the board. “Each play will be reproduced a second after it has actually happened,” the Star News promised in 1929, when Chicago played Philadelphia. Boxing matches also drew fans to Chestnut Street. On February 27 , 1930, a large crowd gathered to hear a local reporter echo the Associated Press account of the Scott-Sharkey fight. “The full and complete blow by lick, duck by dodge, feint by fall, and jab by jolt details will be megaphoned from the Star News building on Chestnut Street.”

In 1935, the Morning Star office moved to the Murchison Building where it remained until moving to 1003 South 17th Street in 1970. (139)

This rare vertical shot shows the 1914 Murchison Building that still stands tall at 201 North Front Street. It was built on the site of banker James Dawson’s House, later the home of Wilmington’s Cape Fear Club. Pembroke Jones’ rice milling plant formerly sat on the western end of the Murchison Building property. The new structure was designed by architect Kenneth M. Murchison, James Sprunt’s brother-in-law, and the eleven story structure was Wilmington’s tallest building for almost a century.

In 1927, entreating Wilmingtonians to put their “idle funds to work,” officers of the bank advertised, “Certificates pay 4% interest and are financially sound. The Murchison stands behind them.” Nevertheless, the bank folded during the Great Depression. The handsome neoclassic building endured and, through the years, has housed a number of important businesses including Hugh MacRae and Company on the tenth floor and the Wilmington Star News on the main floor and mezzanine. There was plenty of space in between, though, and many other businesses, attorneys, local physicians and dentists had offices behind the frosted glass of the old wooden doors. If a visit to the doctor wasn’t enough to cause queasiness, the yo-yo effect of the old elevators was. Of the three, locals knew the one closest to the river made for the smoothest ride. African American women ran the busy elevators, pulling the metal cage doors shut and closing the smooth main doors with a lever. (550)

Here, Walter Corbett totes a basketful of treats along Chestnut Street. On Saturdays, he carried his specialties, fried chicken and individual pies, to Union Station at Front and Red Cross streets, and to the City Market. The Corbett brothers, Walter and John, and William D. Polite, James Sprunt’s butler, were good friends. In 1922, when Mr. Polite, an etiquette teacher and entrepreneur, organized the Waiters and Cook Catering Association, Inc., the three of them worked together and Walter served as financial secretary. Walter James and John E. Corbett were sons of Isaiah Corbett of Ivanhoe. The brothers served in World War I and are buried in National Cemetery.

Wilmingtonian Kenneth McLaurin had his first working experience at Walter and Edith Corbett’s house at 201 South 13th Street, where they operated a tourist home and eating establishment. McLaurin’s job was to bring in coals and wood for the fire and make trips to the Colonial Store, a grocery near 17th and Market streets. “In the days before open accommodations, that was the place to stay,” said McLaurin. “The Corbetts played hosts to many celebrities: Mahalia Jackson, the Globe Trotters, the cast of ‘Amos and Andy’ and Lloyd Price.” Years later, when Kenneth McLaurin was principal at Laney High School, he brushed shoulders with a celebrity in the making: student Michael Jordan.

The Cape Fear Club looms in the background. Established in 1866, it is the oldest men’s social club in North Carolina, and some members believe, in the entire South. Membership perks include club ownership of several paintings collected and contributed by Henry Walters, and dining privileges to feast on Wilmington’s tastiest fried chicken and flounder. (49)

Wilmington architect J. F. Leitner designed Union Station (on right, at Front and Red Cross streets), Building B (on left), and a catwalk connection. He was assisted by Kenneth M. Murchison who also designed handsome railroad terminals in other cities: Hoboken, Baltimore, Scranton, and Jacksonville, Florida. During construction, Leitner recommended discarding the 1856 brass bell that tolled night and day atop the old station. Local folks protested and it became part of the new building. In 1956, the bell was featured on Don McNeill’s Breakfast Hour, a nationally syndicated radio show. By today’s standards, Union Station was a dressy place. In the 1920s, most men wore suits and hats and women wore dresses, hats, gloves and a new style shoe they called “cantilever” and we call high heels. The brass bell rang five minutes, on the minute, then for five seconds, heralding every departure.

Wilmington native Jessie Rehder did not romanticize Union Station in her 1956 novel, Remembrance Way. “The railroad station in Cape Fear looked like the end of the line, which it was. … Nothing in the station seemed ever to have been new. Under the shed the plaque for those who fell in the Civil War had not as yet been replaced by a shaft in honor of those who died in 1918. The old lady with the Cape jessamine shook her finger at a laggard porter but shook it slowly, for nobody here ever would be in a hurry.”

The upper floors of the building housed corporate offices, including that of ACL president Champion McDowell Davis. His favorite colors, silver and purple, dominated his workspace and decorated many trains. During World War II, so many people filled the rotunda that passengers could barely get through the crowd. In 1942, two tons of heavy ironwork was removed from the second floor balcony and sacrificed for scrap for the cause of War II. Union Station was demolished July 11, 1970. (165)

The three-story North Carolina Sorosis building (now razed), located at 116 North Third Street, was next-door neighbor to Wilmington’s City Hall. The Wilmington branch, chartered in 1895, had little more than a dozen members at the time. The ladies studied art, music and literature and gave liberally to worthy local causes. About 1900, club members began operating a library in the Odd Fellows Building. Members served as volunteer librarians and books were rented for a few cents a week.

When the city established a public library at City Hall in 1907, the N. C. Sorosis donated 1700 books. In addition, the Sorosis sponsored music festivals, the 1921 outdoor drama “Pageant of the Lower Cape Fear,” fruit and vegetable exhibits, garden contests and the Baby Parade at the Feast of Pirates festival. The group established Travelers Aid, a baby clinic and the James Walker Memorial Hospital auxiliary. Mrs. Rufus Hicks led several members on a crusade to transform Greenfield Lake from a millpond to a showplace. After years of campaigning, the city purchased the site and worked with the Sorosis to beautify the grounds.

In the absence of a permanent public gallery of art, the N. C. Sorosis building filled a vital role by hosting numerous art exhibits and lectures. It was the first place in which Claude Howell, in 1936, formally exhibited his work. Other artists who showed their paintings at 116 North Front Street included Delbert Palmer, Mrs. Will Rehder, R. C. McCarl, Mrs. Harry DeCover, Irene Price, Mrs. C. M. Weathers, Mrs. Ernest Bullock, Atha Hicks Josey, and Emma Lossen. The N. C. Sorosis also celebrated National Art Week by hanging small exhibits in local stores. The club hosted traveling shows, particularly the N. C. Artists’ Exhibits, and scheduled lectures by artists. Club member Phila Calder Nye, a Wilmington native who published an important book, Art History in Outline (1901), deserves much credit for spearheading and defining the N. C. Sorosis’ art program.

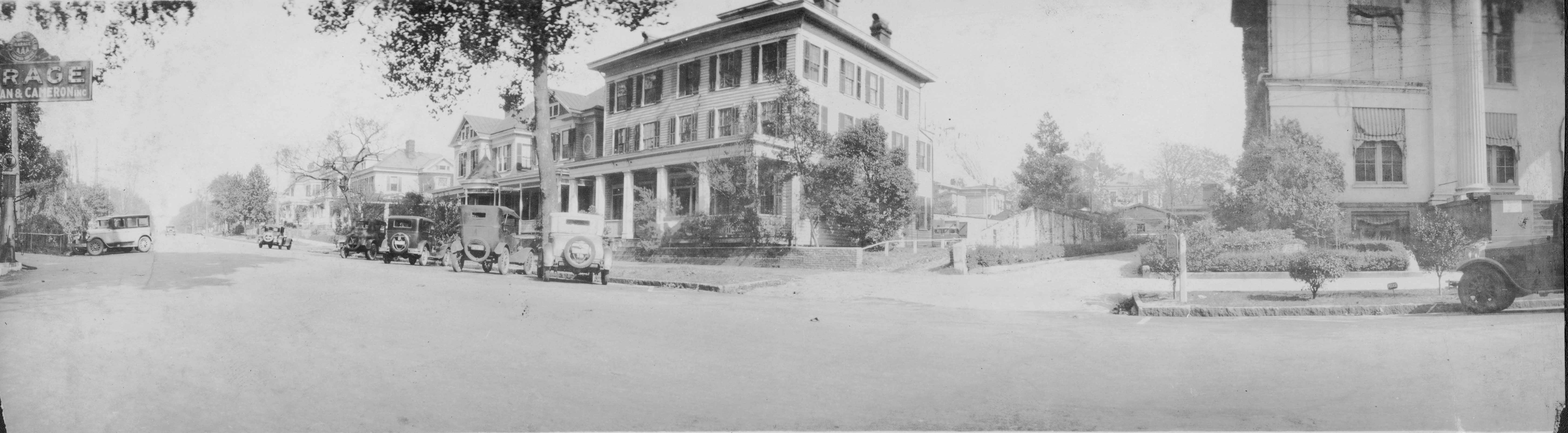

The “Garage” building on the left was the home of MacMillan and Cameron. Today the name Cameron graces buildings all over Wilmington, and as far away as Lexington, VA, but it all started in this one automobile service station on North Third Street. The roots of the business go back to W. D. MacMillan, Jr. and the livery stable business he ran at 107-115 North Second Street, just behind this property. When Mr. MacMillan converted his stable into an automobile dealership, his blacksmiths automatically became Wilmington’s first horseless-carriage mechanics. A young man named Bruce B. Cameron (1890-1944) went to work for Mr. MacMillan, about 1908 and learned the brand-new industry. His early customers included Lee Simmons, with his Thomas Flyer; Monsignor Christopher Dennen in his Hudson Twenty; and A. L. Council, driving a 1909 Cadillac Touring Car.

In 1915, when only 25 years old, Bruce Cameron went into business for himself, selling gasoline and automobile accessories. He had a natural gift for business and soon partnered with Henry MacMillan, W. D. MacMillan’s brother. The 1923 MacMillan and Cameron Garage, designed by architect James B. Lynch, was a revolving door for Wilmington’s motorized citizens. The new company even offered financing: “Our Time Payment Plan is becoming more popular every day. Equip you car with the best tires on the market and pay as you ride.”

When Henry MacMillan died in 1920, his widow, Jane Williams MacMillan, became vice-president of the company, an unusual position for a woman of that era. She proved herself quickly and even published articles about her work. “Getting a Garage Known” earned her ten dollars when it appeared August 1928, in Automotive Merchandising. Both owners enjoyed entertaining, and company parties were lavish affairs, often hosted in the banquet room on the second floor of the garage. In 1930, MacMillan and Cameron celebrated its tenth anniversary with a party in the ballroom of the Hotel Cape Fear.

MacMillan and Cameron opened other service stations around town, including the Sans Souci, a station that opened November 1, 1923, on the northwest corner of Ninth and Nixon streets. “Bruce Cameron spared no pains to make the station attractive,” stated the Morning Star. One item marketed at Sans Souci would have taken the edge off weary travelers: laughing gas.

It’s difficult today to imagine Bruce B. Cameron’s foresight and the magnitude of his business. For several years, it was the only enterprise in town to offer a full line of automotive needs. “It wasn’t like it is today,” said son Bruce B. Cameron, Jr. in 2000. “Now, you can buy a battery on every corner.” (884)

Wilmington City Hall, at 102 North Third Street, was built in 1854 according to the Italianate-Classical Revival design of New York architect John M. Trimble. James F. Post served as supervising architect, and Robert B. Wood, John Wood, and George Rose, as builders. Credit also is due to the individuals who commissioned it. Their opinion of Wilmington is ever stamped in the imposing structure with its large portico and massive Corinthian columns.

The building was designed to accommodate a theater, the cost of which was underwritten in part by Wilmington’s Thalian Association, formed in 1788. John M. Trimble, known for his fine theatrical designs, created a beautiful space, rich in decoration and warm in feeling. According to long-time director, Tony Rivenbark, the new theatre, known variously as the ‘Opera House’ or ‘Thalian Hall,’ opened on October 12, 1858 with G. F. Marchant’s Company of Charleston which was brought in as the resident company for the first season of the ‘splendid new temple of drama.’ One of the highlights of the evening was the unrolling of the drop curtain painted by noted scenic artist William Russell Smith of Philadelphia which today is on display in the Parquet Lobby.”

In 1939, a short-lived effort formed to demolish City Hall and replace it with a civic auditorium. Like the 1936 demolition of the old post office, it would have doubled as a Depression easing make-work project. Local women protested by making a human chain around the building. One of the ladies, a very privileged one at that, emphasized her vote for historic preservation by threatening to lie down naked in front of the building. The streetcar tracks running along Princess Street provided transportation to suburbs like Winoca Terrace and Winter Park. Mundane rides became joyrides during summer when beach cars, painted bright orange-yellow, made daily runs from Front and Princess streets to Wrightsville Beach. (798)

Captain Samuel Potter’s House, at 211 Market Street, was still new in 1844, when presidential candidate Henry Clay delivered a speech from its balcony. “The wide street, for a considerable distance on either hand, was one dense mass of human beings, whilst the balconies, windows, etc., were crowded with ladies, all eager listeners to the words of the great statesman. Never was such a scene, or anything approaching it, witnessed in Wilmington,” wrote James Sprunt.

The two story building barely visible on the left is Hughes Brothers. The building on the far right is the P. R. Smith Motor Company, now Harold Wells and Sons. (922)

Edward Kidder and his younger brother Frederic moved from New Ipswich, NH, to Wilmington in 1826. A few years later, Frederic returned to New England where he made a name for himself as an author and historian. Edward remained in Wilmington where he prospered and married Connecticut native Ann Potter. They built this New England-style house at 101 South Third Street, on a double lot that ran all the way through from Third to Fourth Street. They filled the adjacent lot with gardens and greenhouses that provided congratulatory bouquets and funeral arrangements to townspeople, gratis, for several decades.

Edward Kidder became one of the most successful lumber merchants in the American South. He was a charter member of the Wilmington Chamber of Commerce and led a successful campaign to establish a Wilmington water works. Mr. Kidder gave liberally to educational charities and efforts to enhance the stays of visiting mariners.

During the Civil War, Edward Kidder’s New England roots gripped firm. Despite enjoying his comfortable place in Wilmington society, he questioned the Confederacy’s position and made definite moves to confound Southern resistance. He lost a few of his local friends, but stayed close to a well-educated, powerful group of Wilmingtonians who, sharing his Northern heritage, were jarred with the concept of slavery and eager to establish a freer America. Ironically, Louis T. Moore took this photograph shortly before the 1924 Confederate Memorial, designed by Henry Bacon, took its place in the adjacent plaza at Third and Dock streets.

In 1915, when Louis T. Moore married Edward Kidder’s granddaughter, Florence Hill Kidder, the wedding took place at the Edward Kidder House. The children pictured here are Mr. Moore’s older daughters, (left, front) Florence Moore (Dunn) and (right) Margaret Moore (Perdew), with their first cousin, Roddy Kidder. Annie Green, the Moore family “nurse,” and Mandy Devon, Roddy’s nanny, attend their charges. (972)

John Allan Taylor (1798-1873), husband of Catherine Harriss, was a shipping agent who owned a Cape Fear ferry service owner, sawmill, tugboat fleet, and a Brunswick County plantation known as The Oaks – known today as Pleasant Oaks.

“The residence of John A. Taylor, Esq., is of marble and brick, and cost some thirty thousand dollars.” stated the Herald, November 17, 1857. Mr. Taylor also built, at the Saint James Church Burial Ground, a marble mausoleum that no longer exists. Many of his other building projects were church related; charitable contributions he gave to building campaigns and repairs for First Presbyterian Church and Immanuel Presbyterian Church. Of Ulster Scot ancestry, also, he served on the Relief of Ireland committee, a group committed to “aiding and resuscitating the dying and starving people of Ireland.”

In 1892, the Wilmington Light Infantry purchased the Taylor house. The WLI was organized May 20, 1853, and from the beginning aimed for distinction. Member Edward Cantwell, the first WLI captain, made Jefferson Davis, U. S. Secretary of War, an honorary member. In doing so, he procured 70 government issued breech-loading rifles and the WLI was spared using ordinary muskets. Handsome in their green uniforms trimmed with orange and gold, the WLI escorted President Buchanan when he visited the University of North Carolina. The marble house became the scene of many fancy dress balls.

From 1956 until 1981, the Wilmington Public Library occupied the John Allan Taylor House. In that capacity, the building was an acoustical nightmare. Librarians insisted on silence, but hard surfaces amplified every sound. Children learned quickly that they must walk softly or find themselves the focal point of a matronly glare. Louis T. Moore spent much time during his later years working within the echoing walls of the marble library. The John Allan Taylor House is now the property of First Baptist Church (on right).

At the time this photo was taken, the number of local residents able to recall antebellum memories was dwindling fast. A writer for a federal program located Emeline Moore, a former slave in the John Allan Taylor household, recalled in the early 1930s: “Miss Kitty had chickens and things, and a cow. The house had more land around it then,” she said. The Taylor property included elaborate gardens, broad curved walks, stables and a greenhouse. George Lamb, a gardener Taylor “brought over” from Ireland, tended the grounds before becoming a Wilmington florist. (912)

City Market, at 110 South Front Street, functioned as the city’s grocery store for decades. These children, (left to right) Harry Alexander Nixon, Velma Elizabeth Nixon, and eight-year old Addie Larnese Nixon, went to the market to help their father, Wesley Nixon, a food vendor who farmed family land on Middle Sound. The children shelled peas and butterbeans and made change for customers. They also delivered fresh vegetables to the Honnet and Empie families. In their free time, they munched on sticky buns made by the Craig sisters and visited a Front Street candy store.

The woman on the right, (unrelated to the Nixons) in the dark sweater is probably Evelina Bennett, a resident of Wrightsville Sound. City Market had only a few good years left when this photo was taken on a Saturday morning in 1936. . By 1940, real grocery stores had taken a toehold.

In the 1930s, Wesley Nixon, his wife, Maggie Whitfield Nixon, and their three children lived on the Carolina Beach Road, near Monkey Junction. Addie Nixon Dunlap stated in a 1997 interview, “I learned to skate on the Carolina Beach Road. It was a quiet, two-lane road at the time. We enjoyed going to the nearby filling station to see the monkeys and to Piner’s Store. Our transportation from downtown was a Greyhound bus and our tickets read ‘Monkey Junction.’”

Addie’s maternal grandmother, Betty Moore Whitfield, daughter of Elijah Jackson Moore, cooked for Col. and Mrs. Walker Taylor, at 714 Market Street. Some of her specialties were beaten biscuits, “every grain to itself” rice, and stuffing. The Taylors gave her food to take home in containers that Mrs. Whitfield called “Thank you ma’am pans.”

Harry Alexander Nixon joined the Navy for four years, then spent 20 years in the U. S. Army. Velma Nixon Bennermen married a serviceman at age 18 and lived most of her adult life away from Wilmington. She died in Wilmington on June 29, 1999.

Addie Nixon Dunlap graduated from N. C. Central in 1947, received a Master of Social Work degree from U.N.C. in 1976 and a Master of Counseling from N. C. A&T in 1983. She worked for the Wilmington Housing Authority and Social Services for many years. (220)

Kenan Memorial Fountain, the centerpiece of Fifth Avenue at Market Street, was created from Indiana limestone and designed by Carrere and Hastings of New York, the same architectural firm responsible for the New York Public Library and other designs commissioned by the William Rand Kenan family. In 1921, William Rand Kenan, Jr. gave the fountain and accompanying walls and benches to the city in memory of his parents, William Rand Kenan and Mary Hargrave Kenan. According to Walter E. Campbell, author of Across Fortune’s Tracks:A Biography of William Rand Kenan, the fountain “represents the close connection between one man’s economic interests, in the Carolina Apartments, and his love for the city at the center of his family’s history.”

In 1953, N. C. Highway Commission engineers decided to remove the fountain, declaring it a driving hazard. Debate had raged for more than a decade as increased automobile traffic seemed to shrink the intersection of the two boulevards. Mr. Moore, a life-long friend of the Kenan family, worked hard to keep keep the fountain and to placate William Rand Kenan, Jr., not only a friend, but an internationally known philanthropist. Suggestions to move it to South Third Street, across from Greenfield Lake, or to the entrance to the Cape Fear River Memorial Bridge didn’t set well with some Wilmingtonians. The local press pushed hard to have it removed, one way or the other. Cousin Owen Hill Kenan, noting that some of the trouble came from drunks and reckless drivers who collided with the the fountain, wrote to Mr. Moore, “ (but) it is always the fountain’s fault.”

Louis T. Moore went on a personal crusade to save the fountain, writing scores of letters to gather support. He also visited his friend and neighbor, architect Leslie N. Boney, and told him the problem. The architect, also a friend of the Kenan family, was happy to create a solution. Boney hailed from Duplin County, the Kenans’ ancestral home, and his wife, Mary Lily Hussey, was named for family friend Mary Lily Kenan Flagler. Working in the basement office of his Italianate home at 120 South Fifth Street, a block and a half from the fountain, he devised a plan to improve traffic flow through reducing the size of the monument by cutting away the lower tier and erecting a high wall.

On November 17, 1952, William Rand Kenan, Jr. wrote Mr. Moore, “I appreciate the trouble you have gone to in connection with the fountain at Fifth and Market and, apparently, you have won and it is going to stay there. My appreciation to you is great.” (791)

William Allen White, author of Woodrow Wilson: The Man, His Times, and His Task, visited the Bellamy Mansion (on right), while doing research for his book. When they were young men, future president Woodrow Wilson and John D. Bellamy, Jr., son of the physician who built this house, were best friends. White called the 1859 mansion “the old South at its apex.”

In 1924, he recorded what he saw inside the house — a house that was still a home.

“Within, on the right side of the hallway, running through the house, are two stately salons – parlors, they are called – furnished sumptuously in Victorian mahogany; here are deeply stuccoed coves, sweeping draperies of velvet hanging from gilded Florentine cornices above the windows, cornices that match the gilded mirrors over the spacious fireplaces at the ends of the rooms; rich old-fashioned carpets upon the floors and bric-a-brac of a grand manner placed around the grand rooms.

“This home must have influenced the youth, must have given Wilson something of that ornate and festal languor that brocaded the patterns of Irish lace over his somber soul.”

The John Dawson House and the Carolina Apartments building sit on the southern corners of the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Market Street. For almost fifty-five years, Mr. Dawson, a native of Belfast, ran a general merchandise business on the northeast corner of Front and Princess streets. A few months before his death, in 1881, Mr. Dawson sold his business to William E. Springer and Company. When this photograph was made, the John Dawson House was home to Mr. and Mrs. (Katie Reston) Adair McKoy, and their two children, Jean Victor McKoy (Graham) and Adair McKoy, Jr.

William Rand Kenan, Jr. and Thomas H. Wright built the Carolina Apartments building in 1906-07. (924)

The Boys’ Brigade Armory, on the southeast corner of Second and Church streets, was designed by architect Charles McMillen and dedicated June 22, 1905. The building was a gift from Mary Lily Kenan Flagler, whose brother, William Rand (“Buck”) Kenan, worked closely with the boys. At the time Mr. Moore took this photo, almost 3,000 youths a month attended programs or played sports in the Norman-style fortress.

The building contained a gymnasium, dressing room, a library of 2,000 books that James Sprunt contributed, reception rooms, offices, an auditorium, bowling alley, dining room, and a kitchen. Riley Moore, an African American cook, served up fine meals for the Boys’ Brigade from 1896 until the 1930s.

Col. Walker Taylor (1864-1937) founded the local Boys’ Brigade on Valentine’s Day, 1896, at Immanuel Presbyterian Church. He based the organization on a similar one he observed in Scotland – the Boys’ Brigade Company in North Woodside, Glasgow. The Wilmington group began with a membership of five, but grew quickly when word got out that Brigade membership offered free 10-day camping trips to Southport, NC.

One of the most notable Brigade achievements took place during World War II, when members contributed to national defense by collecting scrap metal. The boys turned in enough iron, 1,418,974 pounds, to build a ship. They named it for the club founder. The S. S. Walker Taylor was launched March 28, 1943.

The Boys’ Brigade was housed in various buildings after it outgrew the armory, its most distinctive headquarters. Col. Taylor’s grandson, Walker Taylor III, serves as a Brigade leader who is sensitive to needs within the community, regardless of color or class. (152)

Copyright: Susan Taylor Block (Text) and New Hanover County Public Library (Photos)

Dear Ms. Block,

I’m working on a book chapter about the Nye family of Fairhaven, Massachusetts–mostly William Foster Nye and his son, Joseph Keith Nye, who was married to Phila Calder Nye.

I’m interested in their marriage. I’m guessing that Phila met Joseph, when he was in North Carolina harvesting porpoises for his whale oil business. It’s possible, though, that they met through their interest in art. I know that they were “estranged,” though I don’t think they were actually divorced. Any light you could shed on this would be much appreciated.

With best wishes,

Beth Luey

Hi Beth,

Go to sblock.net – then search for Calder and/or Nye.

There are some Calders here still. One or two of them are attorney.

They’re a great family.

Best,

Susan Block