by Susan Taylor Block

(Click on photos to magnify.)

Louis T. Moore looks like a young poet in this photo, taken in 1906 when he was a student at the University of North Carolina. Times were tamer then: His sister and widowed mother accompanied him to Chapel Hill and lived in the village from 1905 to 1906. He took lodging in Old East dormitory.

Mr. Moore was a busy college student, being a member of the Kappa Alpha Fraternity, the Di Society, and the University Press Association. He won a letter playing baseball. At times, he served as head cheerleader.

Louis Moore’s love of trees was encouraged during his college years when legendary tree enthusiast Dr. William Chambers Coker was teaching botany and laying the groundwork for the University of North Carolina’s Coker Arboretum. In time, Moore would emerge as Wilmington’s most ardent tree conservationist. In addition to preserving many of these community heirlooms, he froze bark and leaf to photographic memory.

On November 22, 1915, Louis T. Moore married Florence Hill Kidder, a distant cousin he had known since childhood. Their wedding took place at the Kidder House at 101 South Third Street. The couple had three daughters: Florence Moore (Dunn), Margaret Moore (Perdew), and Ann Moore (Bacon).

Pictured in shadow, Louis T. Moore photographed the Washington Oak, on Highway 17 at Hampstead, in 1925. Longtime oral tradition states that George Washington napped under the tree en route to the Wilmington leg of his 1791 Southern Tour.

Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution snared much attention for the live oak when they dedicated a granite marker there shortly before this photo was taken. Pictured are (left to right) Moore’s daughters, Florence Kidder Moore and Margaret (Peggy)Yeamans Moore, with their cousins, Elise and Hope Wishar.

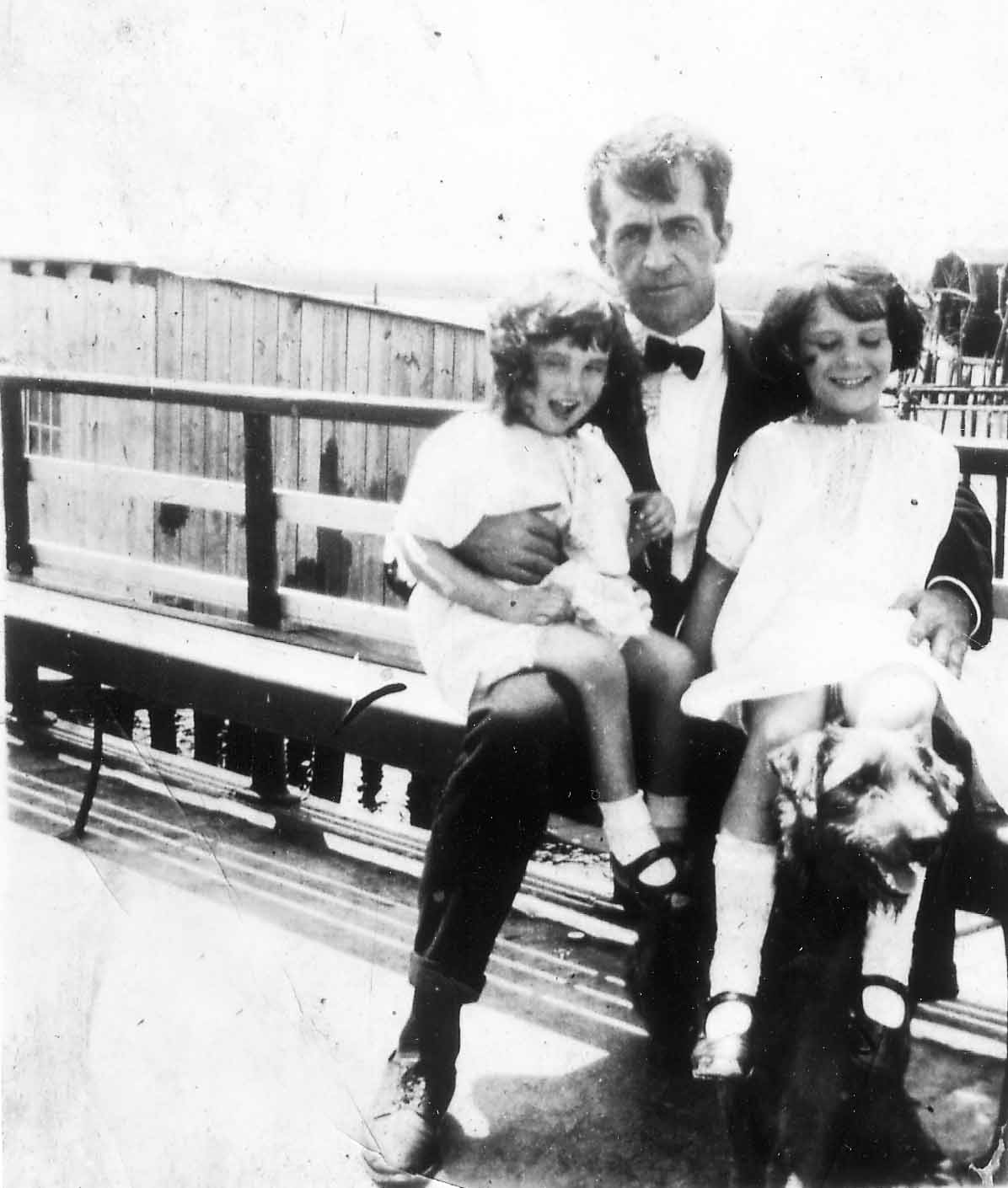

Louis T. Moore holds his two young daughters (left to right), Peggy and Florence, on the steamer Wilmington about 1925. It was rare for him to be on the front side of a lens, even when his involvement in civic and regional activities merited his inclusion, because he remained selflessly and happily obsessed with preserving the present for the future through photographs. “I remember riding around with Daddy and he always had that camera with him because he thought he might miss something. If he saw something that caught his eye, he’d jump out and click the picture,” Florence said in 1999.

An automobile ride was still a big deal in the 1920s, especially if you were packed into a touring car with a bunch of buddies. Louis T. Moore enjoyed taking neighborhood youngsters on a spin. “Those children were probably taking their lives into their hands because my father was not the best driver,” said daughter Peggy Moore Perdew.

Louis T. Moore’s identification list for this 1907 photo notes the children as, left to right:

“Moonby Moore (lower); Bob Williams (upper); little Moore boy (Mody’s first cousin); Little May Moore (Mody’s first cousin); “Bully” Louis Moore (upper) car owner; Mary Hardin (Mrs. Lenox Cooper), standing; Cameron MacRae; Martin Schnibben; Roy (“Sappy”) Craig (married Mary Giles Bellamy); Calvin Wells; Tom Wells (both Wells are standing side by side); Bill French (seated); Luke French (top); John Hardin (top) (French and Hardin are standing side by side); Emily MacRae; Eugene Hardin; May Latta Moore.” (Photo by Lee Greer Studio.)

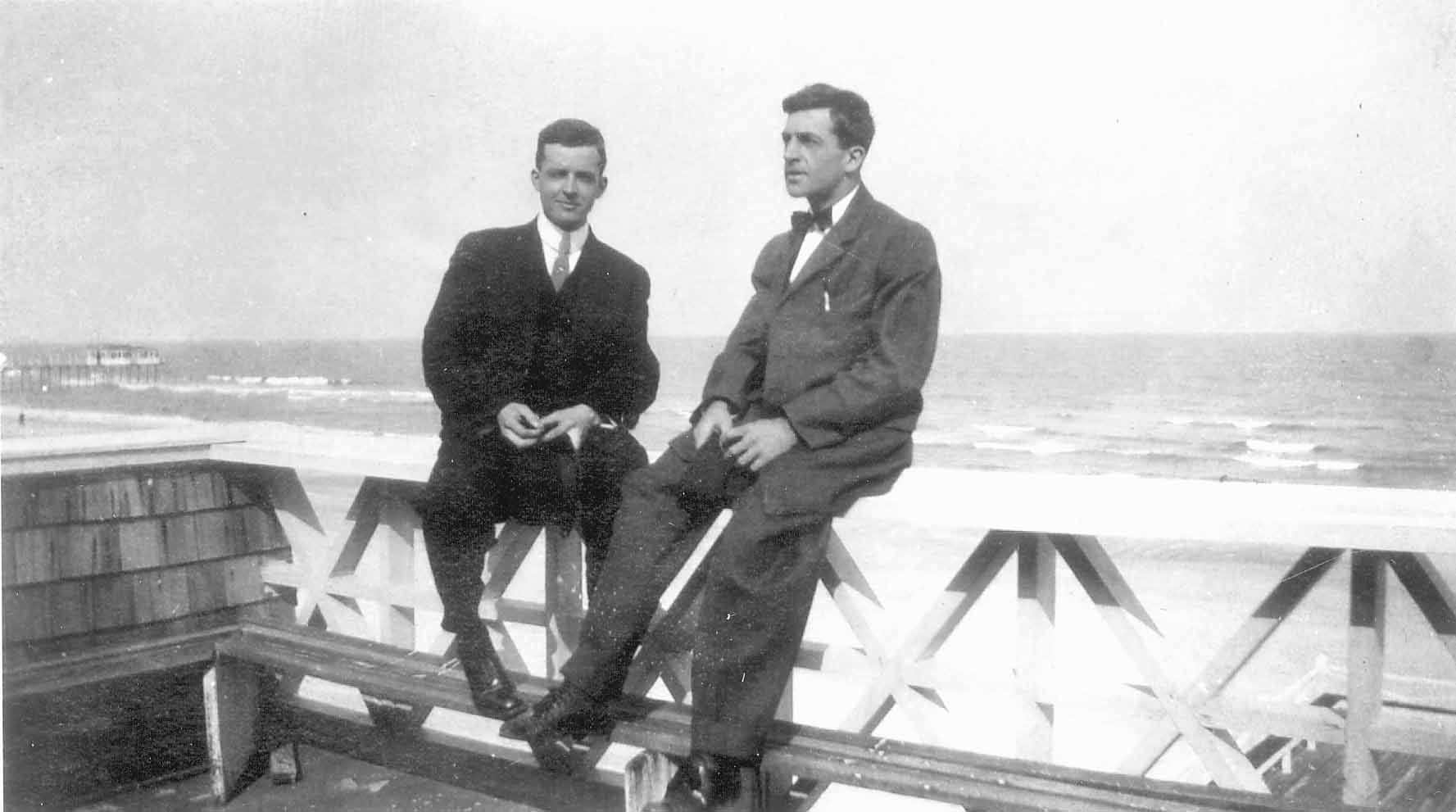

Louis T. Moore relaxes at Lumina with an unidentified friend, about 1932. For Mr. Moore, “leisurewear” meant suits, and he preferred blue ones. He bucked the trend of wearing four-in-hand ties. “Daddy never wore anything but a bow tie,” said daughter Florence, in 1999. It was his signature.

Florence Kidder Moore (1888-1971), pictured here at their Wrightsville Beach cottage in 1928, is remembered for her fine cultured voice and elegant ways. She edited much of her husband’s work, including Stories Old and New of the Cape Fear Region.

The pretty ocean view was obscured from time to time when large sand dunes formed. To the delight of the Moore children, mules rode the streetcar from Wilmington to the Moore cottage to help plow the dune.

Mr. Moore took this beautiful photograph of his youngest daughter, Ann Kidder “Nannie” Moore (Bacon) at Wrightsville Beach, about 1932. Her two sisters were old enough to take stock of their father’s babysitting methods. They reminisced in 1999.

“Can’t you see Daddy walking down the boardwalk, holding on to Nannie’s shirttail?” asked Florence.

“Yes,” said Peggy. “He’d hold onto the hem of her little dress – and he’d read the newspaper. Why he didn’t walk right off the boardwalk, I don’t know. But that’s the way he babysat.”

Here, Mr. Moore’s oldest daughter, Florence, poses with his youngest daughter, Ann, at Orton Plantation, about 1937. The house was built in 1725 by their ancestor, “King” Roger Moore, but Mr. Moore seldom mentioned it.

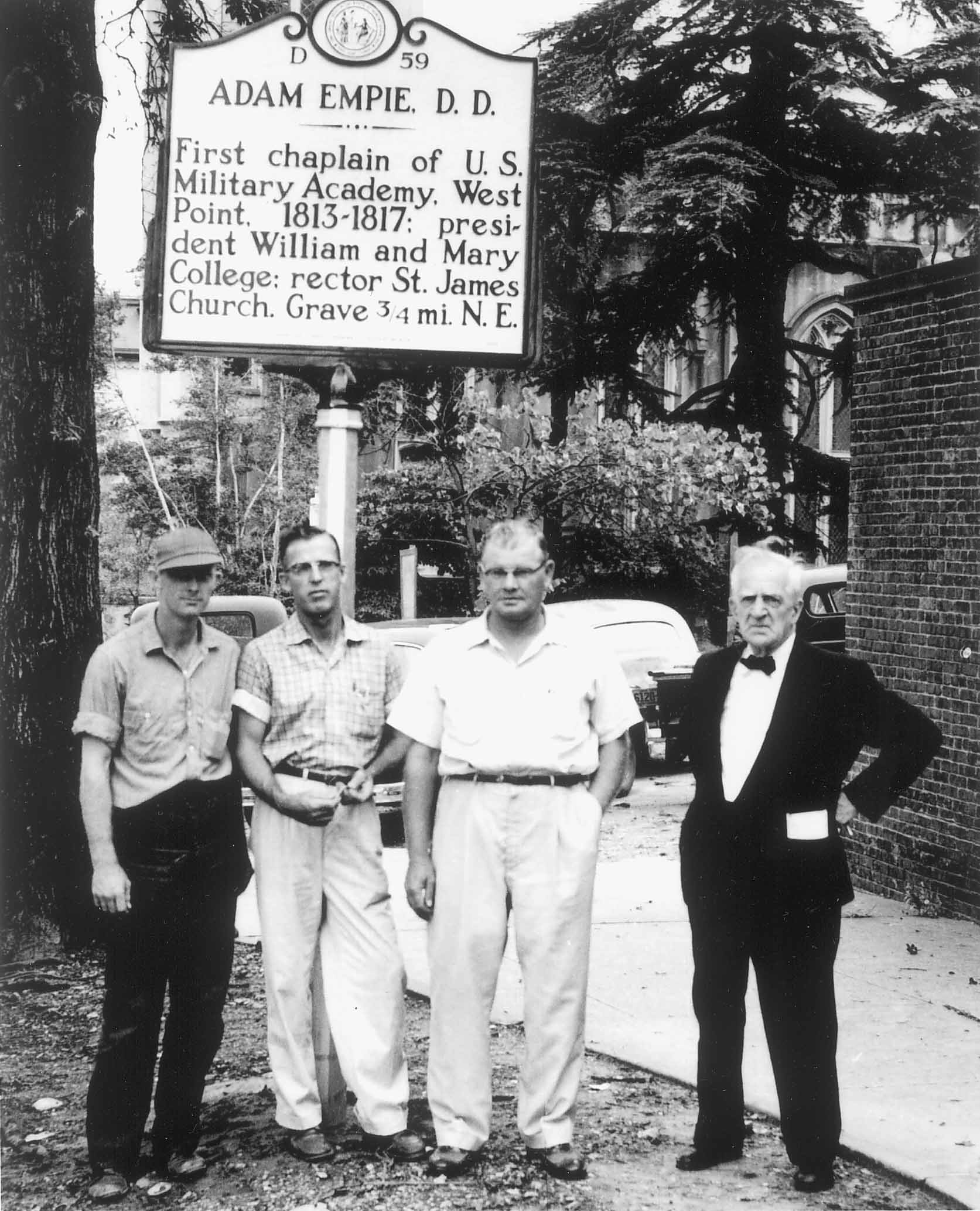

Tenacity showing, Louis T. Moore poses with city employees, (left to right) J. H. Holden, foreman; A. I. McLean, sign supervisor; and L. R. Merritt. The men installed a memorial plaque for the Rev. Adam Empie (1785-1860) near St. James Church on South Third Street. Empie served as rector of the church, the first chaplain of the U. S. Military Academy, and as president of the College of William and Mary. Louis T. Moore obtained the plaque after researching Empie’s life and writing scores of letters to state officials. Due almost entirely to Mr. Moore, southeastern North Carolina has more historic roadside markers than any region in the state except the Research Triangle.

Louis T. Moore stands by the grave of Captain William A. Ellerbrook, a German immigrant who operated a tugboat on the Cape Fear River. Ellerbrook, also a volunteer fireman, was called to a fire at the corner of Front and Dock streets one night in February 1880. His faithful collie dog accompanied him and waited outside while his master battled the flames. Suddenly, hearing Ellerbrook moan, the dog raced inside to find his master penned under a heavy timber. The collie tugged on Ellerbrook’s coat in a desperate attempt to drag him from the inferno. Tragically, both man and beast died. When firemen located the collie, they found a piece of cloth torn from Ellerbrook’s coat in the dog’s mouth.

After Capt. Ellerbrook’s funeral at St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, he was laid to rest at Oakdale Cemetery with his precious dog cradled in his arms. “Daddy loved the story of the fireman and the little dog. We were raised on that story,” said Peggy Moore Perdew in 1999.

James E. L. Wade, chairman of the War Memorial Association, and Louis T. Moore, chairman of the New Hanover Historical Commission, examine the county’s newest monument. The text of the monument, praising all veterans from New Hanover County, was written by Mr. Moore. The handsome granite and bronze memorial, located at Greenfield Lake, was unveiled, July 29, 1950, by Charles Chadbourn and Rabbi Karl Rosenthall. The observance marked the 25th anniversary of Wilmington’s purchase of Greenfield Lake, a move for which Louis T. Moore campaigned for years.

Others who participated in the 1950 ceremony were the Reverend Dr. B. Frank Hall, the Rt. Rev. Thomas H. Wright, the Rev. Mr. Ira H. Jeter, and Mayor Royce McClelland. After poems, prayers and speeches, the crowd “numbering 300 of all color and creeds,” joined in singing patriotic songs, accompanied by the U. S. Marine Band from Camp Lejeune. Today, an American flag flies over the marker, located near the intersection of Lake Shore Drive and West Jackson Drive.

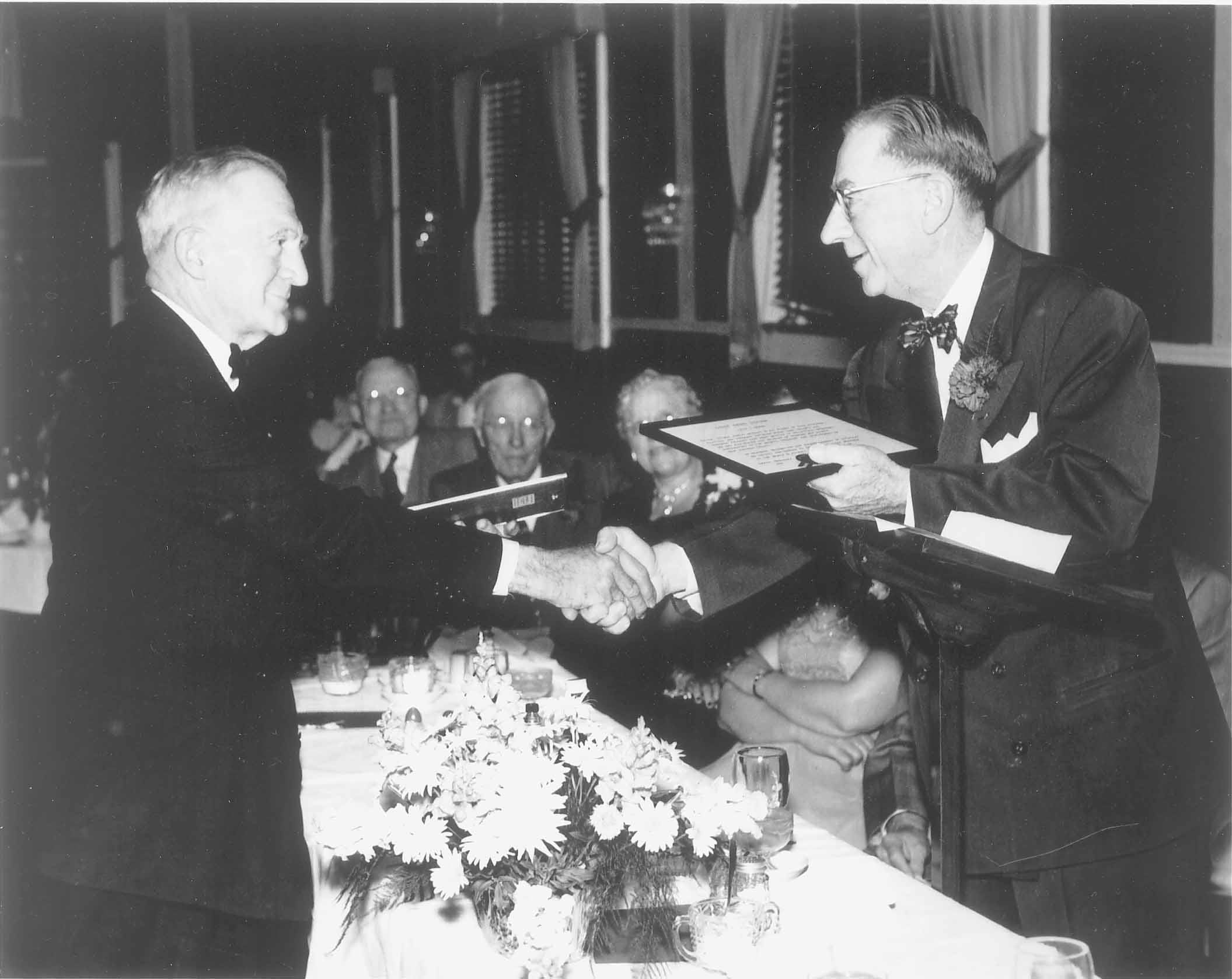

President Farrar Newberry presented Louis T. Moore with the Woodman of the World award for national achievement in the field of history and conservation of “soil, minerals, forest, and wildlife,” on April 17, 1953. In the background are Wilmington Mayor E. B. White, Addison Hewlett, and author Crockette Hewlett.

Much of Mr. Moore’s work stays with us. If it weren’t for his well thought-out endeavors, Wilmington would have fewer live oaks, scant roadside history plaques, less written history, and 1,000 less panoramic photographs of the 1920s and 1930s. His herculean efforts to promote and improve the city changed the reality and perception of Wilmington in ways that still trickle down to benefit us today, an effect predicted by J. Laurence Sprunt, Wilmington and Orton Plantation, in 1952.

“Your unceasing efforts to preserve for future generations all the good and inspiring events and personalities connected with Wilmington is of incalcable value to the community,” wrote Mr. Sprunt to Louis T. Moore.

“Your fight to keep the record straight in spite of so many odds and willful indifference, would have been given up long ago by anyone not having the blood of ‘Those Pestiferous Moores’ in his veins.

“There will come a day when your efforts will be appreciated in proper measure.”

Truly, Louis T. Moore was “Mr. Wilmington.”