by Susan Taylor Block

(Click on photos to magnify. Double-click and scroll to see more.)

Though St. James Parish, created in 1729, is older, church construction in Brunswick County predates the first St. James Church building by 22 years. Work on St. Philip’s Church, at Brunswick Town, began about 1737, but the struggle for completion went on for decades. Financial woes plagued many early Anglican projects. The Rev. James Moir, who split his time between St. Philip’s and St. James from 1740 to 1746, said he usually was “paid in commodities not worth the trouble of receiving.”

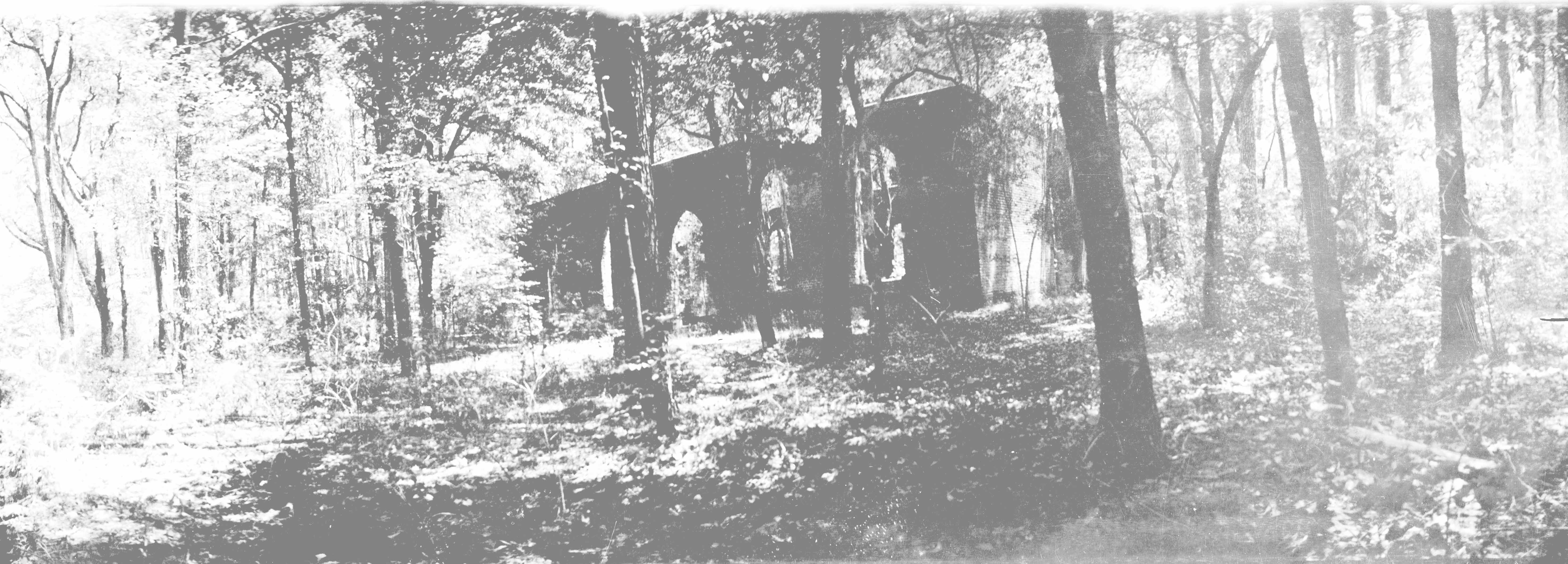

Governor Arthur Dobbs obtained funds for a roof in 1760 when he announced plans to designate St. Philip’s “His Majesty’s Chapel in North Carolina.” Just weeks after the roof was in place, a summer storm destroyed it. A lottery and the partial proceeds from the 1748 Spanish pirate episode provided enough cash for repairs. (see “Ecce Homo,” below.) Governor Dobbs died in 1765 and was eulogized at St. Philip’s while guns fired at Fort Johnson, a temporary battery in Wilmington and “His Majesty’s ships lying in the river.” Dobbs was buried within the walls of the uncompleted church.

James Sprunt was fond of the old building and employed Wilmington photographer J. W. Buck to take pictures there on several occasions. Louis T. Moore turned up a little known fact about the church: In 1745, drunken disturbance at St. Phillip’s Church were penalized with a $2.50 fine. (586)

Construction on the first St. James Parish building began in 1751 but was not finished until 1770. It sat partly in Market Street and its modest style and appointments disappointed some of Wilmington’s fancier Anglican visitors. British forces added injury to insult when they used the church as a stable during the Revolution. By the early 1830s, aesthetics and space necessitated a new building. Communicants William C. Lord, Dr. Thomas H. Wright, and Dr. A. J. deRosset were leaders in the building campaign to construct a new church at 1 South Third Street.

After spirited debate, the church settled on a plan to erect a Gothic Revival building. Just as a single steeple points skyward, Gothic Revival buildings such as St. James provide many visual aids to higher thoughts. The finials, crenellated parapet, pointed arches, and vaulted ceiling, all are in agreement.

The walls of Gothic churches are full of processed light, because the solid structure is heavily perforated to make way for spacious windows of translucent glass. Light becomes a verb within a stained glass window, bringing to life the darkest hues – and beautifying what is mundane. After study, even a small detail from a stained glass window can revisit the mind, bringing delight. Many windows include scenes from Scripture, thus adding instruction to mere beauty.

Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-1887), a well-known Philadelphia architect, created the design for St. James. A decade later, in 1850, Walter earned a permanent space in American history when his design was chosen for the United States Capitol dome. John S. Norris, known for his artistic designs in Savannah, served as supervising architect for St. James.

Existence in a hurricane belt can be tough on architectural adornments. Originally, five finials, like the ones on the tower, lined both sides of the roof of St. James. By 1855, only two side finials remained. The four tower finials have been the lone survivors for generations now, and even they have to be replaced from time to time. (103)

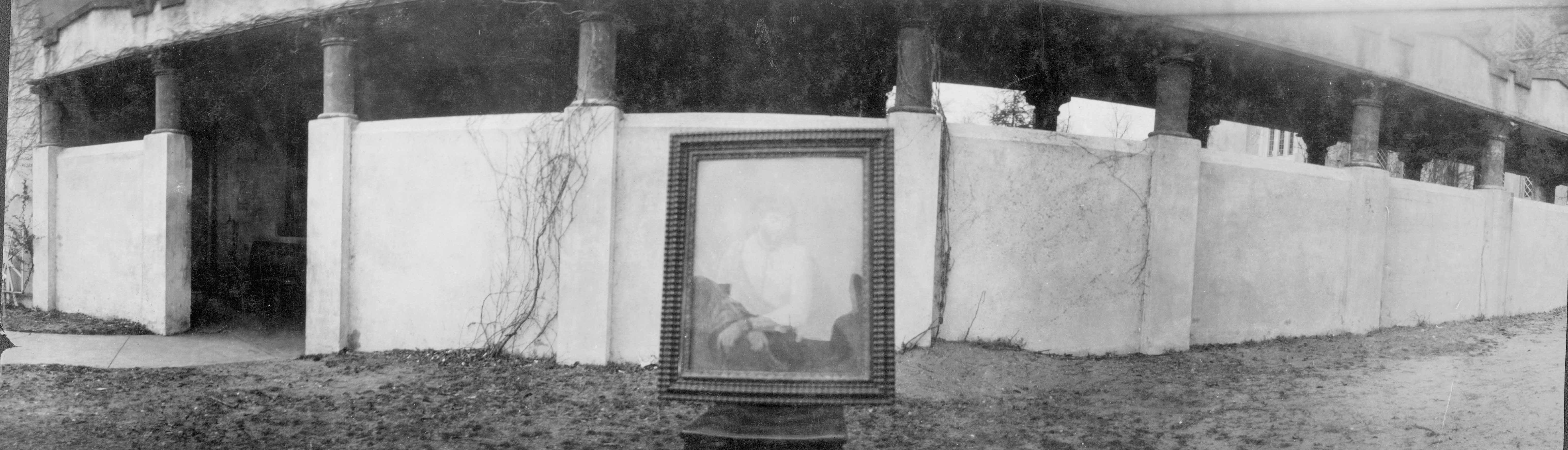

Stealing is bad enough, but snatching religious art might make guardian angels jump ship. In 1748, Spanish sailing vessels paid a pop visit to Brunswick Town. One of them, the Fortuna, sank when its powder magazine exploded during a skirmish. Sixty men went down with the ship, but Brunswick militia members, one being “King” Roger Moore, salvaged pilfered cargo. Colonial government officials decreed the booty be sold and part of the proceeds go toward the completion of churches in Wilmington and at Brunswick. However, rather than sell Ecce Homo, (“Behold the Man”) the painting was given directly to St. James Episcopal Church.

Mr. Moore’s camera was not equipped to make pictures indoors, so he photographed Ecce Homo outside St. James Church, in the cloister. The result is a clear photo of the surroundings, but a filmy image of the very clear painting of Jesus wearing the crown of thorns. Oils in the paint combined with sunshine to create the diaphanous effect. According to Mr. Moore’s daughter, Peggy Moore Perdew, “Prickly roses, those flat-type roses with awful thorns, used to lace the cloister, but then roses and thorns are appropriate symbolism for a church.”

This photo appeared in Wilmington, the Port City of North Carolina, a booklet written largely by Mr. Moore, and published by William L. deRosset, in 1937. In 1950, art historian Stephen Bourgeois suggested Francesco Pacheco (1564-1654) painted Ecce Homo. Pacheco was the father-in-law of Velazquez – and art tutor to Alonso Cano, the “Spanish Michelangelo.” (785)

The St. James Burial Ground lies quietly on the left. The churchyard is a remarkable neighborhood of remains ranging from those of Wilmington’s most celebrated early citizens to sailors who died unexpectedly while in port. Colonial hero Cornelius Harnett and playwright Thomas Godfrey, who wrote the first American drama, “The Prince of Parthia,” are buried here, too. Mr. Moore wrote: “Many also believe that the grave of the last British Governor, William Tryon, is in this old graveyard.”

Louis T. Moore liked to point out this sleepy section of Fourth Street between Dock and Market, as the site of a bloody 18th century duel. Two high-profile Wilmingtonians, Revolutionary War hero, Major Samuel Swann and merchant John Bradley, faced off July 11, 1787, after a disagreement concerning a British stranger Swann befriended. Swann, a renowned marksman, intentionally grazed Bradley in the hip. After Bradley was hit, he shot Swann through the head. Swann was buried in St. James Burial Ground, once known to church members as “God’s Acre.”

The steps of the Temple of Israel are visible on the right. The downtown fire station, once located on the northwest corner of Fourth and Dock streets, sat far left. Today, St. James’ Perry Building sits on the site. Designed by the late Herb McKim of BMS Architects, the new structure is as close kin to the 1839 building as today’s economy allows. (135)

The Bishop’s House at 510 Orange Street was built around 1905. Another dwelling that stood on the site had been home to Episcopal bishops since 1870. Five bishops of the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina lived at 510 Orange Street: The Rt. Revs. Thomas Atkinson, A. A. Watson, Robert Strange, Thomas C. Darst and Thomas H. Wright. Today, the bishop of the Eastern Diocese of the Episcopal Church in North Carolina lives in Kinston, North Carolina, and 510 Orange Street is a private residence. (150)

Church officials knew they were playing with fire when they decided to build at 121 South Third Street, on the northeast corner of Third and Orange streets. “It stands on what is called the Thunder and Lightning Lot, because of an old stable which once stood on this lot and which was frequently damaged by lightning,” James Sprunt wrote of the 1861 Georgian-style First Presbyterian Church building. However it wasn’t lightning, but faulty wiring that ignited the building, New Year’s Eve, 1925.

The Louis T. Moore family lived only a block away, at 308 Dock Street. They joined other neighbors to watch the horrible beauty of white-hot flames against a black sky. The towering spire became a huge torch that could have ignited several residences if it hadn’t of crashed into the street. “We were terrified the steeple was going to fall on our house,” said Florence Moore Dunn, in 1999.

A year before the fire, author William Allen White visited Wilmington while researching his book, Woodrow Wilson: The Man, his Times and his Task. He interviewed people at the First Presbyterian Church who remembered the days when Wilson’s father led the congregation and young Woodrow was just the preacher’s son. “The old people of Third Street remember the young man walking sedately into church on Sunday morning with his mother upon his arm,” wrote White.

“He was almost, but not quite, an exemplary youth. But that church, domiciled in a rectangular edifice with high Gothic ceiling supported by six Gothic pillars of dark oak with the gallery for the slaves in the rear, with a prosperous, well-dressed congregation that even to this day bows clear to the forward pew rail when the parson prays, …that church gave Tommy Wilson, who soon was to become Woodrow, his philosophy of life.” (173)

Many members of First Presbyterian Church wished to rebuild the church to resemble Samuel Sloan’s original design, but minister, Dr. A. D. P. Gilmour, and several other strong church leaders led a campaign to build a church that would bear some resemblance to European cathedrals they had seen and admired. Dr. Gilmour won the battle, but fifty years after the new church was dedicated, there still were a few elderly members who pined for the old design. The first building at Third and Orange streets did sit more gracefully on the alloted space. However, the new structure was positively grand in both size and building materials, despite the fact that the final bill totaled about $500,000.

Renowned architect Hobart Upjohn designed the new building with its dazzling verticality. It features handsome stonework, amazing stretches of heart pine, and dazzling verticality. This photo probably was taken soon after the building was dedicated, November 18, 1928. On that day, the Reverend John Wells borrowed some fitting words from the prophet Isaiah to describe Wilmington’s cathedral: “The shadow of a great rock in a weary land.” (Isaiah 32:2) Doubtless, he was thinking spiritually, but praying the building would be as fireproof as an ancient rock was not a bad plea either, especially considering First Presbyterian Church’s architectural history. (166)

Wilmington’s Baptist congregation dates back to at least 1808. By 1825, they worshipped at the Baptist Meeting House, at 305 South Front Street. The building that has survived. Known today as Baptist Hill, is has been a residence for over a century.

Under the leadership of the Rev. Mr. John L. Prichard, the congregation purchased the land for a new building in 1857. Designed by architect Samuel Sloan, the building period stretched from 1859 until 1870. Despite the political and financial turbulence of that era, the building emerged magnificent.

With a majestic Gothic Revival exterior of brick, stone, and slate, the interior is a veritable museum of heart pine. The signature towers, the tallest being 197 feet high, are landmarks. The image of strength the building exudes is not deceiving. The walls are over three feet thick.

Today, First Baptist Church owns the John Allan Taylor House (on left), too. (See “Downtown Wilmington” chapter.) (912)

The Ebenezer Baptist Church building (on right) was built atop the basement of the congregation’s 1896 structure, designed by James F. Post. The Negro Welfare Association was organized at Ebenezer Baptist Church in 1923. The current Ebenezer Baptist Church building, at 2929 Princess Place Drive, is large and well-attended.

Many laundresses took their work home. Here, Elizabeth Gibbs and two children pose in the 200 block of South Seventh Street.(214)

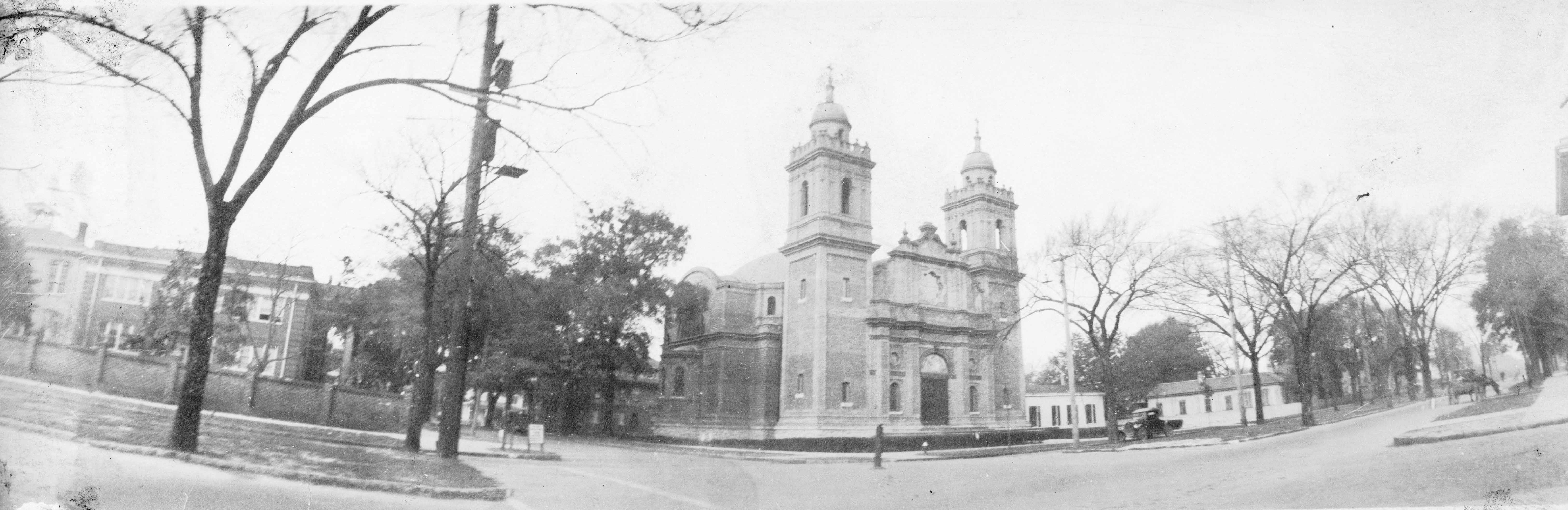

The Saint Mary Church at 220 South Fifth Avenue is a Spanish Baroque cathedral that has served members of Wilmington’s Roman Catholic community since 1911. Unique in Wilmington’s slate of church design and materials, St. Mary speaks of other places and other times. In fact, Ecce Homo, would have fit right in here.

Architect and contractor Rafael Guastavino, with his son Rafael, built an engineering marvel in which an intricate canopy of mortar-anchored tile hangs high above an interior constructed without nails or wood or steel.

Saint Mary Catholic Church boasted a good school, too. In the 1920s, the student body included future concert pianist Amos Allen; artist Hester Donnelly; model and professional dancer Katherine Meier; banker and Wrightsville Beach mayor Michael C. Brown; and historian, E. Lawrence Lee, Jr.

Dr. Lee reminisced in 1996 about old-fashioned discipline: “The priest at St. Mary’s was really the head of the school and every now and then he would take an unruly boy, never a girl, out to the woodshed and strap him. The boy would return to the class looking very embarrassed. The embarrassment was worse than the pain. It was effective.” (874)

Windermere Presbyterian Church on Eastwood Road began far across town, in 1865, and was called Immanuel Presbyterian. The first building was a small house on Wooster Street, between Fifth and Sixth streets, donated by John Allan Taylor, a member of First Presbyterian Church. In 1886, the property was swapped for a lot on the corner of Front and Queen streets and prospects of a bigger structure.

A new edifice was dedicated in 1891. By 1895, the church boasted 123 members, 115 of whom moved their membership from First Presbyterian. On February 14, 1896, Col. Walker Taylor, John A. Taylor’s grandson, organized the first meeting of the Brigade Boys’ Club at Immanuel Church. About the same time, Florence Bonitz organized a kindergarten at Immanuel Church that she directed for 25 years.

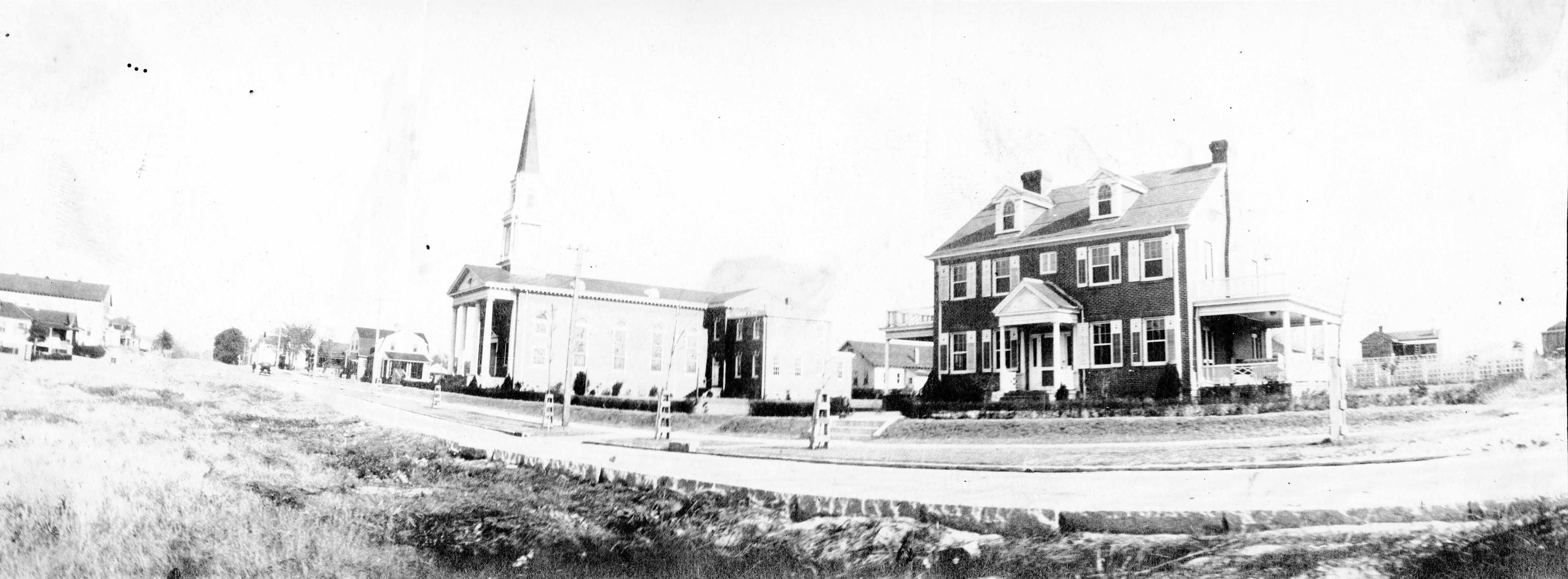

By 1920, the congregation had once again outgrown its home. This time, another Presbyterian, cotton merchant James Sprunt, served up a furnished brick colonial church and manse for Immanuel’s congregation. James F. Gause designed both. The church and manse, located at Fifth and Meares streets, cost $150,000. The congregation contributed $5,200. The dedication took place on February 12, 1922. “The rich mellow-toned Austin organ provides the music and presents an artistic front which completes…the interior…,” read the program. (925)

St. Andrew’s-on-the-Sound took part of its name from Sarah Jones Walters’s name for her waterfront home, “Airlie-on-the-Sound.” The 1924 church was designed by architect Leslie N. Boney and built by contractor U. A. Underwood. Mary Giles Davis donated the 2.5-acre tract, land passed down to her through her Wright ancestors. Construction costs totaled $20,000 for the Spanish mission style building located at the “Shell Road Crossing.”

St. Andrew’s-on-the-Sound was built by the same talented men who constructed Pembroke Jones’s Italianate hunting lodge at Landfall, and crafted the garden sculptures within Airlie. Most of the workmen lived in the Wrightsville Sound area. The men themselves gave a beautiful stained glass window to the church, in memory of Pembroke Jones. They made the cross that sits atop the church, too, and hoisted it into place using pulleys and brute strength.

Mrs. Walters gave a substantial donation and contributed all proceeds from early Spring garden tours she offered at Airlie. The Rev. Dr. Frank Dean collected the remainder, mostly from Wrightsville Beach and Sound residents, and members of St. James and other Episcopal churches: the Rev. Alexander Miller, Anson Alligood, Thomas Morton, C. C. Chadbourn, Anson Alligood, William G. Dizor, W. A. Taylor, Mary Cowan Davis, Mrs. M. W. Divine, Mrs. Eloise Burkheimer, Annie Kidder, Jeanie Strange, Dr. Galloway, William Lord, A. T. St. Amand, Robert Tapp, and Mrs. Morrison Divine.

“It is recalled with feelings of awe how the gardens were opened year after year sometime ago, for the benefit of the little church at Wrightsville,” stated the Morning Star, in 1934. “It is a much loved story of those who know it to believe that these flowers really built this church. The church is, too, a real little beauty spot and the circumstances of its existence make it more interesting.”

The beauty of St. Andrew’s-on-the-Sound was enhanced by Rudolph A. Topel (1856-1937). Both Airlie’s gardener and a member of the church, Mr. Topel was able to channel extraneous materials from Airlie to St. Andrew’s. “The grounds surrounding both church and parish house of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church at Bradley’s Creek are being beautified by the transplanting of forest trees. Maples and other fine specimens of native trees are being removed to the church property.” (156)

St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Bath, founded 1734, is the oldest church in North Carolina. The building also housed the first library in the state. Alexander Stewart, an Anglican minister who served St. Thomas and surrounding parishes from 1754 until 1771, had ties to Brunswick Town. He was personal chaplain to his cousin, Governor Arthur Dobbs, who resided in Brunswick from 1758 until his death in 1765. Anglican priest, author, champion of Native Americans and African Americans, and benefactor to St. Thomas, Alexander Stewart is buried beneath the church building and memorialized in a roadside marker.

This photo was taken shortly before the Reverend Mr. A. C. D. Noe, a friend of Mr. Moore’s, spearheaded restoration of the building. (621)