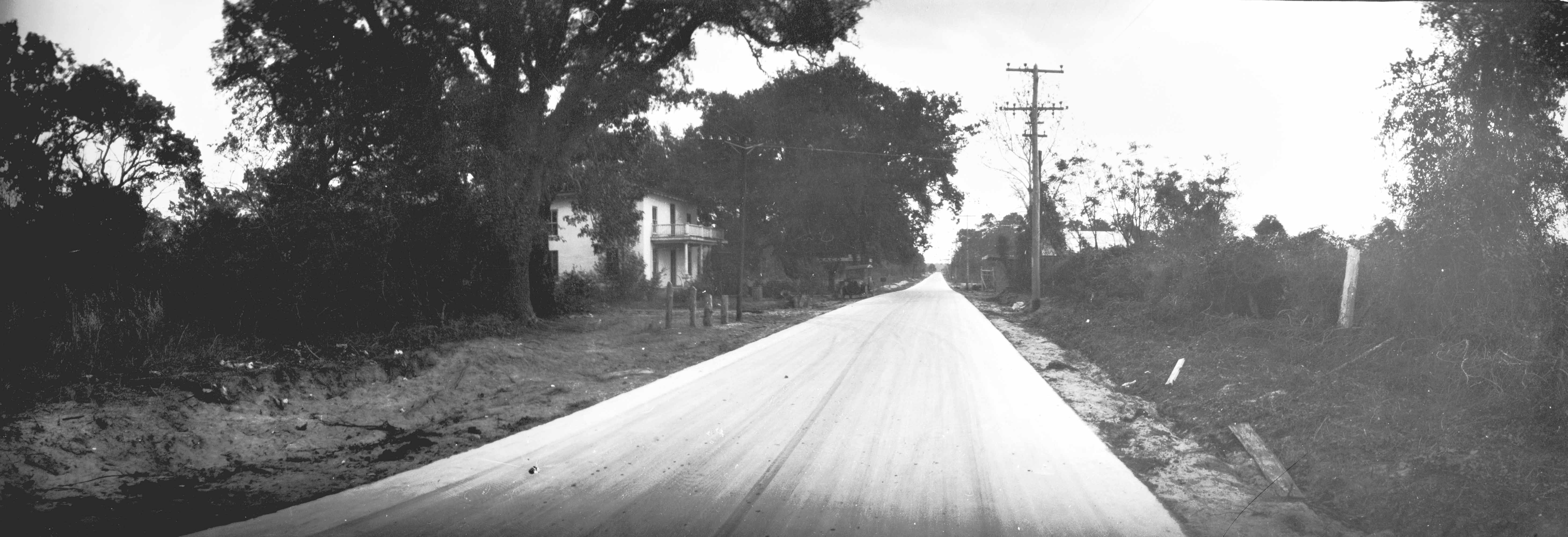

In 1928, Carolina Beach Road became a state highway and improvements followed. New things need names so Mr. Moore recommended “Fort Fisher Junction” for the spot where Highway 421 meets Highway 132. The New Hanover County Commission agreed, but the name stuck for only a few months before a new sign was erected: “Myrtle Grove Junction.” In the early thirties, it changed again, this time to what Louis T. Moore termed in 1959, “the rather unpleasant sounding name of Monkey Junction.” This photo was taken on the Carolina Beach Road, near the intersection, but it does not show the pet monkeys nearby that attracted customers to their owner’s automobile service station. (722)

In 1935, Snow’s Cut transformed Federal Point from a peninsula into an island. The mile-long channel connects the Intracoastal Waterway and the Cape Fear River, just 15 miles north of the river’s mouth. The waterway was named for Major William Arthur Snow, an American hero who led his brigade in the Battle of Belleau Woods, France, in 1918. Even after suffering a neck wound, Mr. Snow labored sixteen hours to bring all his men through the combat zone safely.

Major Snow supervised the creation of the Intracoastal Waterway from Beaufort to the Cape Fear River link, completed in 1930. Locals coined, “Snow’s Cut,” but the Department of the Interior made the name official in 1944. Originally, Snow’s Cut was 200 feet wide, but now has broadened to around 600 feet. In its infancy, the land on either side was delightfully barren. (179)

Crowds of people waited on the Carolina Beach boardwalk daily for the Freeman family fishermen from nearby Seabreeze to return with their choice catch. Seabreeze, a popular African American resort, was located just north of Snow’s Cut. Ten thousand North Carolinians celebrated Labor Day there in 1933, a typical year. “So great was the crowd of negro visitors at the resort that all articles of eating and drinking were sold out in short order with the result that last night there was nothing for sale, not even soft drinks,” wrote one journalist.

“One of the things that I remember most was Mr. Freeman’s fishing boats that came from Seabreeze,” recounted Wilmingtonian Frederick L. Block, a summer resident of Federal Point throughout his childhood. “Mr. Freeman and all the people who worked for him were black. They had lived there at Seabreeze, a beach community for African Americans, for a long time. Mr. Freeman’s men were hard workers, and consistent. There were three fishing boats, all painted forest green at that time. Anywhere from one to three boats went out every day. Each boat was manned by two to three men. They docked behind Fergus Seafood Market, a block south of the Pavilion on Carolina Beach.

“There was only one outboard motor between the three boats, and most mornings the boat with the outboard motor would pull the other two boats along with it. They would go to a special spot off Fort Fisher and fish from daybreak until early afternoon, and then they would go back to their spot behind Fergus Fish Market to sell their catch. As a young boy, I would go with my mother several days a week to buy very fresh fish. We would watch the ocean from our porch and wait to see when the boats would return. They sailed back because the prevailing wind was from the south. The billowing sails were visible for miles.” (86)

The boardwalk was quieter than usual when this photo was taken, about 1929. It was around that same time that a tiny resort near Morehead City announced it also was adopting the name “Carolina Beach.” Louis T. Moore responded swiftly. His letter writing campaign denounced the duplication as the source of “unjustified and endless confusion, coupled with possible diversion in traffic to which the town of Carolina Beach is legitimately entitled.” They gave up. (88)

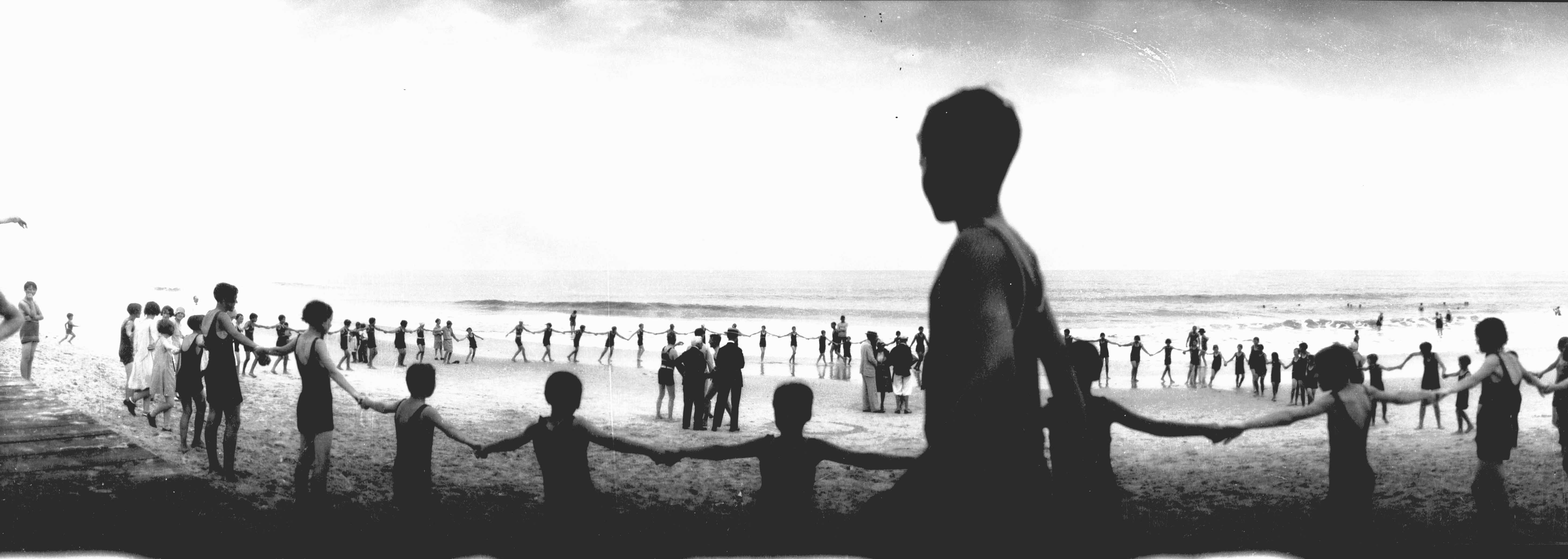

Sunday School “excursions” generally alternated location, visiting Wrightsville Beach one year and Carolina Beach the next. Here, a young group plays “Tap,” a variation of Ring Around The Roses, at Carolina Beach. This photo appeared in the Wilmington Star, May 4, 1930, in a Chamber of Commerce promotion that claimed, “Wilmington is the trading center for 200,000 people.”

Many local retailers treated employees and their families to a day at the beach, too. One business, famous for its strong work ethic, loosened up one afternoon a year. “The Belk-Williams Store closes its doors at 1 o’clock today for its annual outing to its employees. This year it takes the form of a picnic dinner at Carolina Beach,” stated the Morning Star, August 2, 1923. (73)

Louis T. Moore wrote his own caption for this promotional photo of Kiddie Day at Carolina Beach: “This is a scene of ‘just another day not wasted away,’ for they are having a good time at Carolina Beach.” The Auburn Greeting Card Company processed 1000 postcards from this photo as an advertisement for the beach and J. W. Plummer’s General Store. The building on the right is the Carolina Beach bathhouse. (704)

As historian, Louis T. Moore knew his photographs would become more valuable over time, but he could not have envisioned their place within the new technology. His photos sail through cyberspace, and the center portion of this image of three sisters at Carolina Beach, in postcard form, pops up frequently on internet auctions. (681)

WPA projects came in all shapes and sizes. Federal funds paid for writers’ interviews with Wilmington’s former slaves, drainage and malarial control ditches, road construction and buildings like Legion Stadium, built for $100,000 in 1937. In 1934, Federal funds also financed boardwalk construction at Carolina Beach. Local funds, the New Hanover Relief Association, paid for the opening of new streets at Carolina Beach, in 1933. (70)

The building on the left is the lunch stand and pavilion at Carolina Beach. Development was sparse on the north end, even before the Great Depression took hold in 1929. That year, there only were six cottages on the extension, but that would change: 150 houses were built at Carolina Beach from 1932 through 1935.

The City of Carolina Beach offered Malcolm McIver, a Wilmington lumber merchant, four oceanfront lots if he would build a hotel to stimulate tourism. McIver, later, a mayor of Carolina Beach, built the Ocean View Hotel (far right), just before the Great Depression set in. It was the only hotel on the strand at the time and boasted 50 rooms “with running water.” The most expensive room cost $6.50 a night.

In 1930, tenants G. L. Edwards and B. D. Bunn, professors at Campbell Junior College, fell short on cash and could not pay their hotel bill. They worked out a trade in which McIver’s son, Mac, Jr., could attend Campbell free of charge. That was the beginning of a very fine education for the young man. Malcolm McIver, Jr. went on to graduate from Louisville Presbyterian Seminary, earned a PhD at the University of Edinburgh, and gained many more academic honors. Dr. McIver served as Dean of the School of Christian Education at Union Presbyterian Seminary, in Richmond, for many years. (87)

The Breakers at Wilmington Beach, a 50-room hotel, was built in 1924. Owned by Mainland Beach Corporation, the general contractor was U. A. Underwood, the plumbing contractor was Wilbur Dosher, and Albert Pick and Company of Chicago provided the furnishings. Orton Hotel employees Charles E. Hooper and Frank Gregson managed the upscale inn that included a barber shop. About 1927, a small pavilion was constructed at Wilmington Beach, opposite The Breakers. It burned May 18, 1930.

The Ethyl-Dow Corporation leased The Breakers and in 1941 made it a club for its employees. E. Cooper Person served as club manager. (673)

In 1934, when Ethyl-Dow opened its new bromine plant at Federal Point, Louis T. Moore was ecstatic. He responded with a large Chamber of Commerce welcome notice in the Wilmington Morning Star touting Wilmington’s ideal climate, power supplied by Tide Water Power Company, deepwater port and “conditions tending to promote health.”

Thomas H. Wright, of J. G. Wright and Son Real Estate, planned a resort development near Ethyl-Dow, but economic conditions of the Great Depression squelched it. (297)

When the road to Carolina Beach and Fort Fisher was completed in the spring of 1929, it greatly pleased Louis T. Moore. He loved driving through the pillars of Fort Fisher, as his daughter, Peggy Moore Perdew, reflected in the 1999. “Once, when I was working in Jacksonville, Florida, Mother and Daddy were preparing to come down for a visit. I thought, ‘What will I do with Daddy? He’ll be miserable away from Wilmington.’

“The McCarthy hearings were on TV so I got a television for him to watch. He wasn’t too interested in that so I thought I’d take him to see St. Augustine since it was historic. He wasn’t impressed. He just kept talking about how wonderful Fort Fisher was.” (842)

Gabriella deRosset Waddell (the older woman) and Archibald Henderson (on left) visited Fort Fisher, and posed near the Oyster Market. At the time, mathematician Henderson was Kenan Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, but he juggled other interests. A household name to many North Carolinians, Archibald Henderson also was an author, historian, and biographer.

As a baby, Gabriella deRosset was tossed from the deck of the Lynx, a blockade runner damaged by Union fire, into the arms of waiting sailors. She and her mother boarded another blockade runner, the Tallahassee, captained by John Newland Maffitt, and traveled to England where they lived for the remainder of the Civil War.

During their stay, they met author and diplomat Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He was so fond of the little girl that he taught her to recite his poems. When Lord Bulwer-Lytton died, he left Gabriella a legacy of a thousand pounds and the copyright to his first drama. (189)

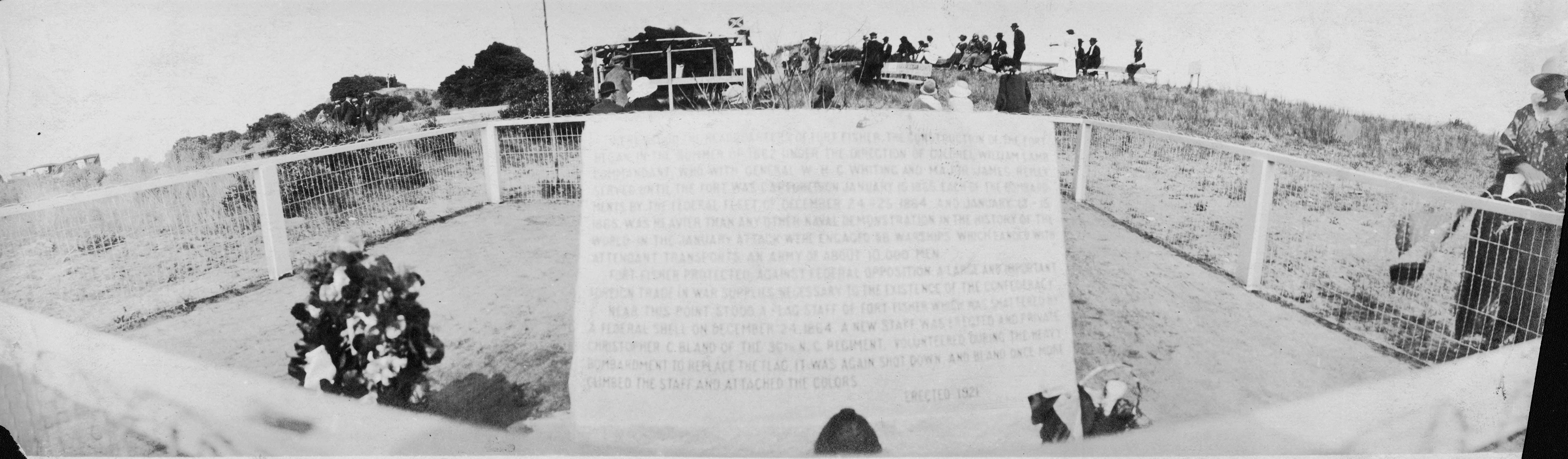

“At the mouth of the river stands Fort Fisher, one of the strongest forts on the Atlantic Coast, as it proved itself in the terrible days of 1865, when Porter and Terry knocked at its doors, and finally burst them open,” wrote travel journalist Edward King, in 1875. So strong was the fort that Wilmington was the last Confederate port to fall during the Civil War and so mighty was the sea battle that it broke all amphibious records and stood as a touchstone until the Normandy Invasion during World War II.

In the early ‘20s, eyewitnesses to the battle, elderly but eager to revisit the mounds, endured an ordeal to reach them. Until 1927, the dirt road from Carolina Beach to Fort Fisher was often impassable. That year, brick salvaged from the First Presbyterian Church building that burned in 1925 was used as the foundation for a gravel road. “The work along Edgar Williams Boulevard, which parallels the ocean from Carolina Beach to the old fort ramparts, is of a permanent nature,” reported the Morning Star, March 22, 1927.

Five years later, a marked improvement occurred when the federal government allocated $400 million for road construction to increase employment.

The United Daughters of Confederacy erected the 1921 monument at Battle Acre. A flag flew over the spot, hoisted daily in the early 1920s by a Miss Hewett, often accompanied by Edgar Williams. (843)

The erosion started in earnest in 1928. “The beach is slowly being washed away by high tides and the famous Fort Fisher mound, which was used as a munitions depot during the naval engagement, is in danger of being undermined,” announced the Morning Star. Despite concerned Wilmingtonians’ valiant efforts, the erosion continued. Currently, a portion of the 1929 highway lies under the ocean.

When Louis T. Moore took these photos, eyewitnesses to the Civil War were still around. During the “late unpleasantness,” a Yankee prisoner-of-war camp was located in Brunswick County, across the river from the Market Street dock. In 1924, Wilmingtonian H. R. Kuhl, one of the guards, recalled a night they were raided. Six men arrived to liberate the prisoners, but were unable to overcome the guards, including Captain Kuhl and Tim Dunden, overseer at Oakdale Cemetery.

Twenty years later, Captain Kuhl met a man on Third Street who identified himself as one of the would-be liberators. The Northerner then went on to divulge the fact that “Lt. Cushing, the naval spy who dressed as a fisherwoman, even got into Fort Fisher, where he chatted with the officers without being suspected.” (183)

Despite the fact that it had its own hotel, the Fort Fisher Beach and Hotel Cafe, the land was still hauntingly beautiful in its desolation. In the ‘20s, black cattle still grazed at Fort Fisher and an early Fort Fisher hermit, a squatter who called himself “Governor of the Fort,” amused visitors and perplexed officials. “Fort Fisher is a mere pile of yellow sand, stiffened by palmetto logs,” stated the Morning Star, in 1930. But for a precious few, the battle was still fresh.

About 1922, future historian E. Lawrence Lee visited Fort Fisher with his father and brothers. Dr. Lee’s grandfather, Major James Reilly, surrendered the fort to Union forces. “When I was about ten or twelve,” said Lee, ” my father took my brothers and me to Fort Fisher. We were standing at Battery Buchanan and there was an old man there. He and my father began talking and it turned out that he had been in the battle and had fought with my grandfather. My father said, ‘These boys are Major Reilly’s grandsons.’ Then the old man fell on his knees and hugged each of us and cried. He showed us the exact site where my grandfather surrendered and told us he had watched Major Reilly walk out with his handkerchief draped over the end of his sword. Just a few weeks after that, my father saw the old man’s obituary in the paper. He had died in Winston Salem.

“I met Col. William Lamb’s son years ago. He said he had grown up under a portrait of my grandfather.” (182)

“The ocean was alive with rockets and lights and it was no pleasant thing to have shells and balls whistling over you and around you,” wrote Captain John Johns of Fort Fisher in 1866.

Mr. Moore caught his own shadow when he photographed this spiny skeleton of a beached ship, about 1925. Five blockade runner wrecks once littered Fort Fisher: the Nighthawk, Modern Greece, Petrel, Douro and Condor. In the spring of 1927, “dredges dragged to light” another derelict at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. The steamship Northheathe was intentionally sunk by Confederates, January 10, 1865, in “an ineffectual attempt to bottle up the harbor” and keep the Yankees away. (184)

At a time when they were fading away rapidly, these aged “Boys in Gray” assembled one more time, at Fort Fisher. In 1928, there were only twenty local Confederate veterans: A. M. Baldwin, T. B. Cox, Michael Thomas Davis, B. F. Hall, J. A. King, J. A. Montgomery, R. W. McKeithan, Henry C. McQueen, W. D. MacMillan, Richard Reaves, R. J. Sykes, William M. Skipper, J. R. Turrentine, D. F. Aman, T. F. Gaskill, J. N. Kennedy, O. H. Kennedy, Asa W. King, W. D. Rhodes and W. L. Williams. Mr. Davis, who lost his right arm during the Civil War, survived them all. Interviewed on his 93rd birthday, May 31, 1939, he said he hoped he would not live to see another war. He did, dying April 13, 1942.

Most were members of Cape Fear Camp, Number 254, an organization founded in 1889. Louis T. Moore’s father, Roger Moore, was a charter member. Southerners revered Confederate veterans and their families in the 1920s and ‘30s. “Stonewall Jackson’s grandson ill,” read a local headline, March 25, 1924.

Louis T. Moore said of Fort Fisher, “This is an historic place marking the fall of Wilmington in the Civil War, which should be seen by all as it is a place where the Union again became “one and indivisible.” His attitude contrasted sharply to some other Wilmingtonians. One local aristocrat, accustomed to taking walks near her downtown home, insisted on crossing the street when she spotted an American flag flying too near her path. (844)

Mr. Moore, a champion of Wilmington’s port, knew well the importance of The Rocks, and called the project “one of man’s marvels.” New Inlet, named without much creativity in 1761, when it was opened by a violent storm, made passage into Wilmington more difficult. Spearheaded by cotton exporter James Sprunt, The Rocks project, begun in 1871, deepened the channel from 7 to 16 feet and allowed larger ships to enter the Cape Fear River.

Civil engineer Henry Bacon, Sr., (1822-1891) designed the coquina and granite seawall and supervised construction. The foundation of the wall across New Inlet was made by sinking a line of “mattresses” filled with logs, brush, shells, and stones. Three floating derricks, one of which was steam-driven, covered the dam with heavy rock. The New Inlet project was completed in July 1881. Eight years later, Bacon finished another dam, twice as long, known as Swash Defense Dam, from Zeke’s Island to Smith Island.

One observer stated its purpose very clearly, in 1907: “The Rocks, which shuts out the ocean from the river.” (194)

Copyright: Susan Taylor Block (Text) and New Hanover County Public Library (Photos)

What a wonderful article! I have always loved Fort Fisher and spent many hours on the beach there swimming, fishing and exploring when I was younger. I have a passion for history and genealogy so found the pictures and information to be very enlightening. My husband is a musician and has performed there with the Eleventh Regiment Confederate Band many times and we always enjoyed the museum and the day filled with history. Thank you for the wonderful story, we plan to pass it down to our grandchildren.

I am a amateur historian who is in the process of creating a you-tube video based on the old Bayview Hotel that once stood on the shores of the Pamlico River. I am seeking permission to use one of the images on your website as a reference to the other old hotels of the 1920’2 and 30’s. I wanted to use the Breakers photo in my video.

This video is not a commercial enterprise but a private one and it’s sole purpose is to educate the public on this Grand Old Hotel of the Pamlico.