by Susan Taylor Block

(Click on photos to magnify. Click again and scroll to see more.)

The Feast of Pirates, celebrated only three years (1927-1929), packed in more ribald, mindless behavior than Wilmington saw before, or has seen since. Based on Wilmingtonian Francis P. O’Crowley’s idea, the festival was the Port City’s collective nod to the Roaring ’20s and a powerful tourist lure. The name was coined by James Owen Reilly, an officer of all three feasts. Twenty thousand visitors joined virtually every able-bodied citizen of Wilmington to celebrate the 1928 festival. “There have not been so many people in Wilmington since refugees filled the city after Fort Fisher fell in the War Between the States,” said one participant.

This photograph depicts Princess Street, looking east from Second Street. This was the “Beach Car” path to Wrightsville Beach, and during holidays or special events like the Feast of Pirates, extra streetcars were added to the local fleet. Here, “Blackbeard” hangs high (left, near Eureka sign) – additional evidence that local promoters left no ballast stone unturned.

Decorated cars, like the one seen on the right, formed a lengthy motorcade and traveled as far as Asheville heralding the festival. Wilmingtonians who participated in the unique “Good Will” trips included Louis T. Moore, Pat O’Crowley, James Owen Reilly, Bruce B. Cameron and Bruce Cameron, Jr. The Feast of Pirates committee members were: Isaac B. Grainger, Walter W. Storm, James F. Post, McKean Maffitt, J. O. Reilly, E. R. Pickard, J. C. McEachern, G. G. Speer. W. J. Haldon, James O’Reilley, O. J. Olsen, H. R. Gardiner, R. F. Walker and J. C. Hobbs. (41)

Here, invading pirates make their way from the Sprunt Wharf to the Market Street dock. Despite the haze (left), the large ferry boats, John Knox and Menantic, are visible. According to Pat Gerken who was one of the participants, the men sang a rancorous version of “From the Land of the Buffalo” as they sailed. When they neared the dock, buccaneers and Wilmington’s “defenders” fought hand-to-hand with grappling hooks and set off smoke bombs in a fixed fight. Today, staging such a production would involve reams of red tape, but things were simpler then: the defenders were area Coast Guardsmen and sailors stationed aboard the U. S. Revenue Cutter Modoc. Government gave its nod of approval.

Participant Pat Gerken also was an actor in the movie, “Wilmington’s Hero,” shot in 1925. It featured other locals: L. R. Hummel, David Sinclair, Maggie Cantwell and Mrs. R. C. Cantwell. In those days, movie ties to Wilmington sprang mostly from connections to local native E. V. Richards, Jr., who became an executive with several film corporations including Paramount.

In 1916, Wilmingtonians Thelma Brooks, Jane Iredell Meares, Muriel Everitt, Katheryn Roach, Warren Sanders, Gus Lund, E. Roscoe Hall and Junior Grimes starred in “Who Will Be Mary?” Wilmington clothier Beulah Meier had a role in another movie, “Goodbye Again.”

Hollywood folks were embedded in the throngs that attended the Feast of Pirates. They filmed many festivities and partook of some of the fun. To date, none of their films have been discovered. (772)

This statuesque pirate is McKean Maffitt, secretary of the Feast of Pirates and Wilimington’s city engineer. Born in 1884, he was first employed, at the age of eleven, as a newspaper carrier for the Charlotte Observer. He attended the University of North Carolina, in 1904, then worked in various cities until 1918, when he moved to Wilmington to manage the water department. A nautical attitude was in order: he was a great-nephew of Captain John Newland Maffitt, Confederate blockade runner, Navy officer, and a cousin of gregarious local shipping merchant, Clarence Maffitt.

McKean Maffitt’s name lives on in the Maffitt-Schnibben House a dwelling at 211 North 15th Street that he built in 1919 – and in the McKean Maffitt Treatment Plant on River Road.

Mr. Moore’s temporary office at 107 North Third Street was abuzz with activity during Feast days. “Information headquarters for visitors will be maintained by the office of the Chamber of Commerce and Louis T. Moore…, and officials of the ‘Feast of Pirates’ will be on the job continuously to dispense any information that might be sought regarding the time or place of any of the sundry events.” Mr. Moore arranged housing for hundreds of guests and invited inquisitive visitors to call his three-digit home telephone number. (609)

“Barbarism Thrills Crowds” was the headline, but Louis T. Moore managed to include a little history in the stew, making the 1928 Feast of Pirates particularly eclectic. “George Washington” traveled down Market Street to reenact his factual 1791 entry into Wilmington. An hour after his arrival, pirates marched up Market Street to City Hall where they placed local dignitaries in irons and declared “three days of mindless merriment.”

George Washington, played by J. Pritchard Orr, and wife Martha rode in a beautiful old carriage pulled by handsome horses. Two lovely raven-haired horsewomen, Dorothy Mallard and Berle Cooper, acted as buglers, riding ahead of the First Carriage.

This photograph, looking down Third Street from Chestnut, gives a sampling of it all, from a pirate in repose, to Colonial “officials.” A festival monitor stands on the right, wearing the customary cap and white shirt. The Wilmington Light Infantry and Boys’ Brigade units took part in the parade. (592)

There were plenty of pretty young women on the parade floats, but a few won special honors: Elsie Blalock, Elizabeth Hoggard and Emma Bellamy Williamson. Here, a float passes between the 1892 New Hanover County Courthouse (left) and the Wallace Building. Almost all buildings featured banners, but at least one hundred businesses decorated elaborately for each festival. The city awarded prizes of $50, $15, and $10 for the best effects.

A lofty Ford sign dominates the background of this photo. Charles B. Parmele owned Chipley’s Universal Motor Company, the Ford dealership on the northwest corner of Third and Market streets, where the Harold Wells Insurance office stands today. Across Market Street, next door to the Burgwin-Wright House, Mr. Parmele operated a used car lot. He sold Chipley’s to P. R. Smith of Fayetteville, who already owned several dealerships in and around Elizabethtown. “It was difficult to get cars to sell in those days, and being in a small town made things harder,” said his wife, Bess Smith, in 2000. “Every now and then, one car would be delivered.”

Mr. Smith purchased the new car business for $30,000 and leased the space back from property owners C. B. Parmele and Thomas H. Wright. Ironically, the same day the sale was announced, October 29, 1929, another piece of business news was the real headline: “Unprecedented Stampede Hits Stock Market.” Despite the “depressed” timing, the P. R. Smith Motor Company was a success, and expanding into a new building, designed by W. A. Simon, in 1931. After P. R. Smith’s death in 1952, managers ran the business until sons Percy and William were old enough to take the reins of the company they called Cape Fear Ford. Under new ownership, it is known today as Capital Ford. (613)

Efird’s Department Store on the southeast corner of Front and Grace streets was part of a 35-store chain owned by Claud Efird. In 1927, a man could buy a fine suit there for just $20. A fashionable broadcloth shirt would cost an extra 98 cents. Efird’s was Wilmington’s dominant department store in the 1920s and 30s, but another outfit, Belk-Williams, would be the survivor. Claud Efird was a talented, powerful boss who did the work of many people. Efird’s Department Store closed after his death. In the mid-1940s, Belk-Williams became Belk-Beery. Under the leadership of W. B. Beery and W. B. Beery, Jr., it grew to be a 20-store operation. (608)

The 1929 Feast of Pirates baby parade winner was Margaret Getty, age 2. Louis T. Moore, Mrs. Getty’s cousin, photographed her in front of the Gettys’ new house at 1909 Nun Street. Margaret’s father, Robert N. Getty, worked for the Atlantic Coast Line as did many of their neighbors. The subdivision known as Ardmore was still new when this photo was taken.

Ardmore was one of several neighborhoods developed by Thomas H. Wright. Mr. Wright acted as developer, realtor, and loan officer. “It is our business to help those who help themselves,” read the ads. “We have secured many a home with very little money down and very easy long-time-like-rent paying plans.”

Margaret Getty Wilson donated her first-place trophy to Cape Fear Museum. Second place went to Robert E. Ferrel, who had just been named first-place winner when the judges caught sight of little Margaret Getty. (217)

Robert E. Ferrel, second place winner in the 1929 baby parade, and his mother, Annie Mae Dement Ferrel, were caught by more than one camera. Long before Dino deLaurentiis arrived in 1982, Hollywood producers (in background) filmed the 1929 Feast of Pirates festivities for three days. They shot footage of the parade and aired it in movie theaters as newscasts.

“All of the children were snapped by the news reel cameraman and it was amazing how well they behaved when they were called to march for the ‘movie men,’” reported the Morning Star. Louis T. Moore and James McKoy were the local promotion team. Leo, the MGM lion, also visited Wilmington and was housed in the rear of the Johnson Motor Company building, on the east side of North Third Street, near Market. (604)

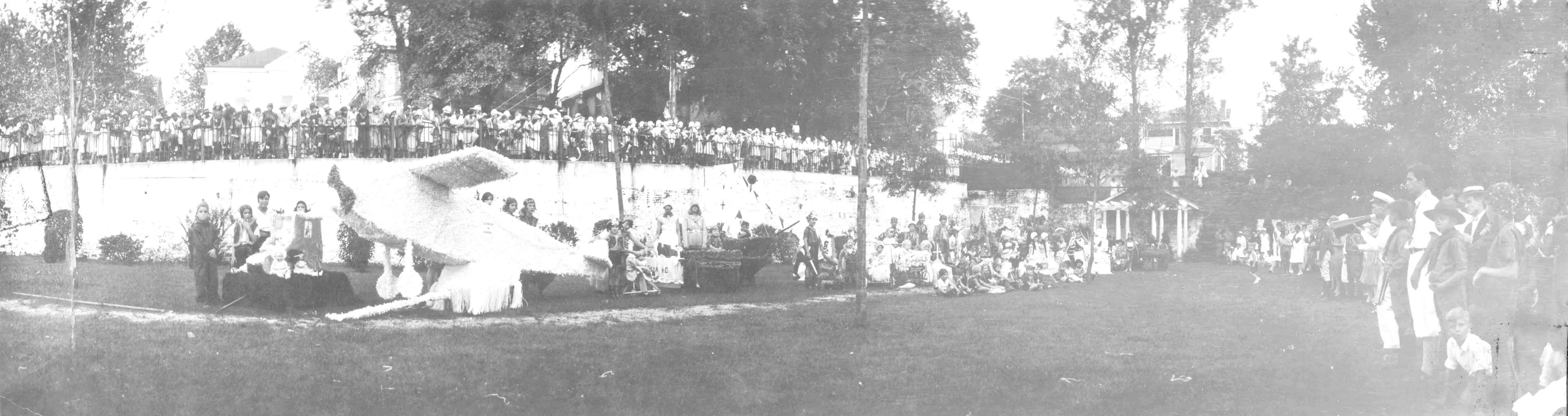

The courthouse lawn at Fourth and Princess streets was the site of the 1929 Feast of Pirates children’s contest. Edwin T. Brinkley and Harriett Harrington won first prize as “Lindy and Anne,” Mr. and Mrs. Charles Lindberg, in an airplane float. Edwin T. Brinkley was broadcaster David Brinkley’s brother. Standing in his clown costume, on the far left, is Jon Knox Wiley, winner in the most unique category.

Costumes bring to mind other celebrations. One participant in the Feast of Pirates mused that it was inspired by the Gasparilla, Tampa’s ribald festival, an event several Wrightsville Beach characters, including Tony Hergenrother, attended annually. It’s an interesting supposition since, in turn, Louis T. Moore believed Gasparilla got its inspiration from Colonial Wilmington’s “John Kuners” (Kooners) and Johnkankus. Young African American men, dressed in brightly colored masks and clothes, strolled the streets of Wilmington, chanting and singing haunting tunes to the music of a banjo, accordion or tambourine. James Sprunt called them “the chief attraction of the Christmas season, especially to the children of 1775-1870.” (800)

Little Jon Knox Wiley looks into the camera while Louis T. Moore snaps a photo of competitors in the costume contest. Children must have exulted in the Feast of Pirates. For three days, adults joined them in make-believe, dress-up and unending recess. Here, young parade participants stand on North Third Street, near Chestnut. The handsome houses on the right and the three-story Charles M. Stieff piano company on the left have all been destroyed. (607)

The 1928 float sponsored by the Stamp Defiance Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution sits still while young girls chosen to ride atop it perform other duties. “Thirteen of Wilmington’s fairest maidens” were chosen to scatter flowers on George Washington’s path, and then accompany him to City Hall where they would board their float. The thirteen flower girls were: Laura Howell, Esther Elliott, Catherine Carr, Lily Van Leuven, Elizabeth Parsley, Edith Roache, Elizabeth Stevenson, Winifred Fisher, Ann Meister, Mary B. Williams, Em Green, Barbara Munter and Helen Kuck.

The three-story North Carolina Sorosis building on the left was opened to the public during the parade as a “comfort station.” Loudspeakers, like the ones seen here, were set up to broadcast Al Smith’s acceptance speech at the Democratic presidential convention. In addition to the ones at City Hall, loudspeakers were posted at the Hotel Cape Fear, the corner of Front and Princess streets and at Second and Market. The speech aired at 7:00 that evening, but festival dancing in the streets didn’t abate until dawn. The favored dance floor was a “waxed” (covered with meal) section of Chestnut Street, between Front and Second. The musical group Carolina Aces provided music and jolly pirates performed a “Grand March” as part of the entertainment. (606)

These two young ladies were part of George Washington’s entourage. The colonial pageant was supervised by the D. A. R. Mrs. Eugene Philyaw, Mrs. William G. James and Mrs. H. T. Fisher directed the short tableau at the U. S. Custom House. (600)

Louis T. Moore recorded not only the Feast of Pirates baby parade but myriad human expressions when he shot this photo on the boardwalk, between the Oceanic and Bud Werkeiser’s Stand. Mr. Moore’s daughter, Peggy, was a little girl then. “I can remember my costume to this day,” she said in 1999. “I had a little wooden sword, painted silver and I wore some kind of knee high boots and little black sateen shorts.” (347)

Boat races were part of the buccaneer blast. Ten thousand people witnessed the competition, the noise of which was deafening. Soon after unmuffled power boats were introduced, Wrightsville Beach banned their use at night and on Sundays. In 1935, a ten-dollar fine was established for anyone operating a boat not “equipped with suitable mufflers.”

At night, Banks Channel was the site of the Feast of Pirates illuminated boat parade. It was an annual event for all three feasts and featured genuine lanterns flickering their flames up and down the waterway. Boats processed from the trestle at Station One to Lumina Pier. The event had a precedent: in 1916, the Feast of Lanterns, sponsored by Hugh MacRae, featured a similar event. (957)

These Feast of Pirates bathing beauty contestants at the Oceanic donned their finest gowns when the sun went down. The Pirates’ “Dance of the Fireflies” took place upstairs at the famous pavilion. Electric bulbs were extinguished and pirates held tiny lights that glittered across the ballroom. “Dancing attracts both young and old to the pavilions each night, where, in the cool ocean breezes and to the rhythm of soft, sweet music from some of America’s finest dance orchestras, the evening passes away only too quickly in such delightful environment,” said Louis T. Moore.

But much of what transpired that last year, 1929, would not have matched Mr. Moore’s idea of a good time. The Feast of Pirates was meant to cause a tourist boom, one that would put Wilmington on the national map. Promoters actually claimed it would challenge New Orleans’s Mardi Gras. Well, if a celebration built around a religious holiday could turn naughty, how much more so, one based on characters dedicated to plundering, self-indulgence and a system of justice symbolized by a plank.

Dancing girls in diaphanous clothing, public drunkenness and a few tricks that got out of hand led to the resignation of Feast officials J. O. Reilly and McKean Maffitt. Mr. Moore must have been mortified: Weak plans were laid for a 1930 Feast. The city allotted $2500 and published pleas for donations, including a poem by Mrs. W. P. Monroe, “Let’s Go Over the Top for the Pirates,” but past antics were not forgotten: “The Feast has found much opposition locally on account of alleged law-breaking said to have transpired,” stated one editorial. The stock market crash of 1929 sealed its fate. Wilmington’s most flamboyant festival was history. In 1933, 25,000 people attended a Pirate’s Carnival at Carolina Beach, but it was a mere shadow of the original. (354)

(Copyright 2010, Susan Taylor Block. Louis T. Moore’s photos are the property of New Hanover County Public Library.)