“Local history is not just local history but human history, world history. The information that you write down, the letters and the maps you keep, these are the drippings of the human spirit and distillings of a man doing his job.” – Paul Green

Although he was a devoted husband and father, in his professional life Louis T. Moore (1885-1961) was married to the Land of the Lower Cape Fear. Wilmington was his love. He couldn’t stop talking about her, he was miserable when away from her, and he bristled when anyone treated her with the slightest hint of disrespect. His devotion was so deep that despite the tension and tragedy of the Great Depression, he pressed on in pursuit of the civic good. Louis T. Moore single-mindedly promoted Wilmington’s industries and tourist attractions while others pessimistically wrote off both the city and their own prospects for improvement.

Though he spoke rarely of his own ancestry, Louis T. Moore had genealogical roots that ran deep as the footings of Cape Fear’s great live oaks. Paternally, he descended from “King” Roger Moore, the Colonial land baron who created Orton Plantation. Louis’s father, Col. Roger Moore, served as commanding officer of the Forty-first Regiment (Third Cavalry) during the Civil War, protecting the railroad line and surrounding properties from Wilmington to Weldon. Col. Moore also led his men in battle at Reams Station, Virginia, August 25, 1864, an effort that won praise from Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Louis Moore’s mother was Susan Eugenia Beery Moore. Her grandfather moved to Brunswick County in the 1790s. Her father, Benjamin Washington Beery, along with his brother, W. L. Beery, owned Beery Shipyard, on Eagles Island, directly across from the foot of Nun Street. Several Confederate iron-clads were built at the Beery Shipyard, including the North Carolina. Benjamin Beery owned another shipyard, too – Cassidey & Beery, located near the foot of Nun Street. His 1853 home at 202 Nun Street still stands.

Louis T. Moore was a seasoned newspaperman when he was only 21 years old, having worked as a correspondent for the Raleigh Evening News and on the staff of the Daily Tar Heel while a student at the University of North Carolina. After returning to Wilmington in 1906, he worked as city editor for the Wilmington Dispatch and for the Star News. Not only did he write well with a steady style and an occasional dash of obtuse humor, but he met the cardinal requirement of a true writer: he couldn’t bear not to write.

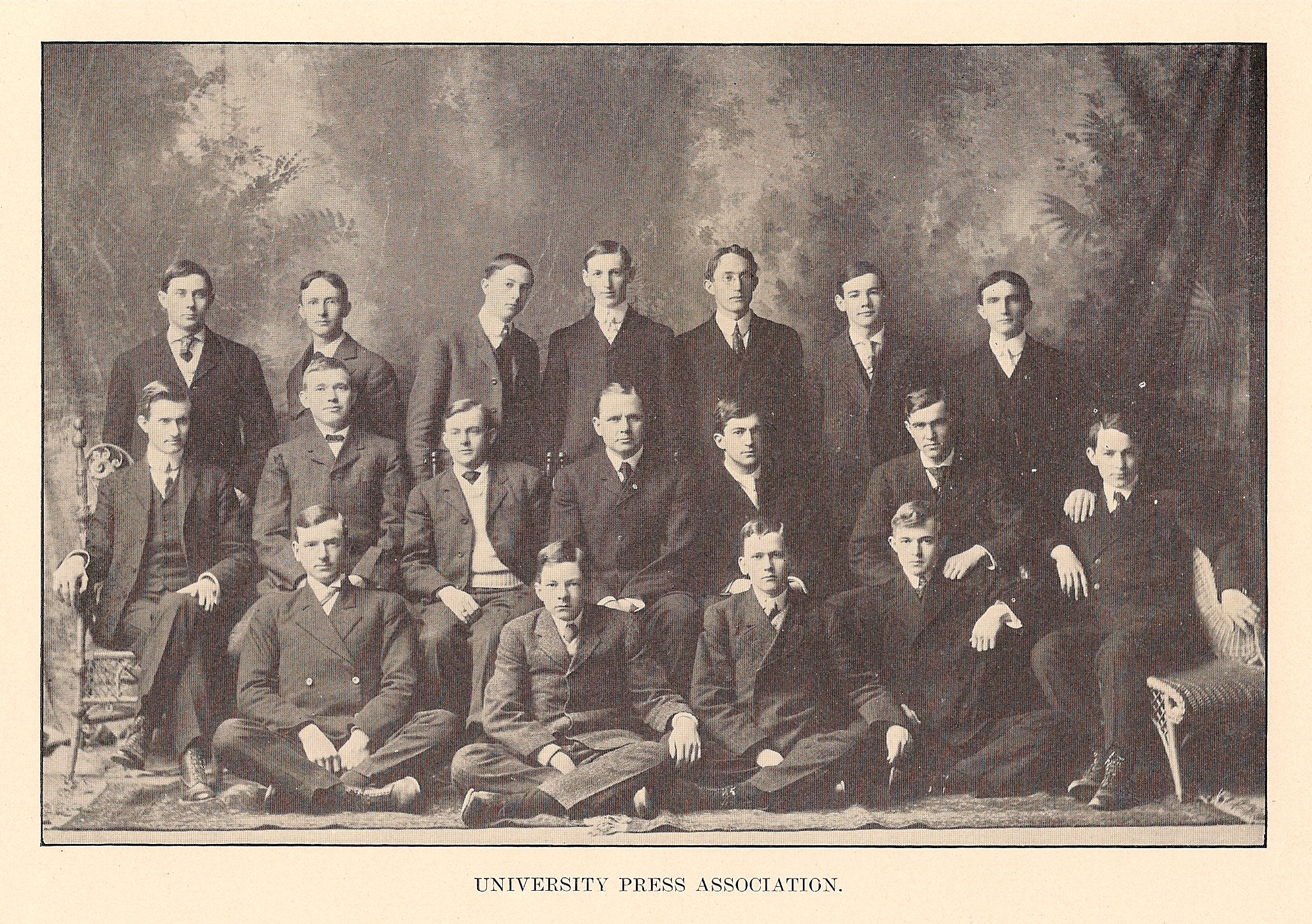

Louis T. Moore (fifth from left on second row) wrote for the Daily Tar Heel and was one of eight Tarheel newspaper correspondents. (Yackety Yack, 1906)

As a young adult, he got little credit for his creative work. Often published without a byline, his lengthy historical essays were quoted and sometimes reprinted in full without the slightest credit. His photos, likewise, were printed in newspapers and magazines nationwide with no credit line. His name does not appear on thousands of postcards made from his photographs. Mr. Moore was in part to blame for the anonymity. Eager to honor others, he usually gave credit away. For example, he attributed virtually all port improvements to James Sprunt, even though Sprunt died in 1924 and Moore worked ardently on port projects until 1940.

While willing to take a back seat as an individual, he could be brash in his efforts to focus attention on the city of Wilmington. He was head cheerleader while a student at the University of North Carolina and the school spirit he exhibited during college simply turned into city spirit after he moved home. He generated enthusiastic backing for Wilmington and verbalized his thoughts quickly and directly to opposing forces.

Louis T. Moore parlayed his writing experience and knack for public relations into engaging the incalculable power of the press in his efforts to promote his home town. While he was Director of the Chamber of Commerce not only did he contribute full-length articles and a steady stream of announcements to state magazines and newspapers, but he convinced Star News publisher Rye B. Page to become the Chamber’s president for several years in the 1930s. The strength and steadiness of Louis Moore’s character and his ongoing relationship with the local press is apparent in these words, taken from an editorial written soon after Mr. Moore’s death: “His consideration for others always was apparent and we never knew a time when his desire for helpfulness did not prevail.”

Mr. Moore’s effectiveness beyond state borders was remarkable. In 1929 and 1930, he secured weekly broadcasts over KDKA radio in Pittsburgh to promote Wilmington and the needs of the North Carolina highway system. His general promotions of Wilmington led to articles in national magazines ranging from Popular Mechanics to Better Homes and Gardensto Literary Digest. His advertising skills spotlighted Wilmington so brilliantly that area industries basked in the glow. It is not surprising that Louis T. Moore was said to be the single strongest champion of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad.

Although local history, preservation, and conservation were Mr. Moore’s chief preoccupations, he also worked diligently to increase revenue for the City of Wilmington. Acting unselfishly for the good of the Cape Fear area, he was a farsighted businessman who worked tirelessly to promote improvements that filled municipal coffers. He saw trade and tourism hampered by inferior highway approaches, an antiquated ferry system, a port that was too shallow, and lack of a maritime protected inland passage – and set about to create change. The process took years of oratory, writing and political wrangling. Though he was criticized for generating little profit within the Chamber of Commerce itself, the City of Wilmington and County of New Hanover eventually profited beyond measure from the dreams Louis T. Moore helped turn into reality.

For the last fourteen years of his life, Mr. Moore served as head of the historical commission. He worked as hard as ever, until the very end: educating and promoting his hometown, always spending more of his own money on postage than the modest honorarium allowed. Letters he wrote not long before his death reflect the fact that he was still researching, educating and promoting.

The late historian, author, and Brunswick Town preservationist E. Lawrence Lee nominated Mr. Moore for the prestigious Charles A. Cannon Cup awarded by the North Carolina Society for the Preservation of Antiquities. Moore received the honor in 1960. Dr. Lee stated, “More than anyone I know, he has long dedicated himself to the history of Wilmington and vicinity and to the preservation of historical landmarks in that area. His interest in written history has been reflected in his constant search for and preservation of documents and other source materials as well as in his writings.” Louis T. Moore died the following year, on November 30, 1961.

Louis T. Moore’s work in the preservation field does live on in many ways, one of the most delightful being the 1000 panoramic photographs he took during the 1920s and 30s. Years after he left the Chamber of Commerce, he retrieved the pictures and donated them to the New Hanover County Public Library. Through them, viewers can step into a simpler world and slip into a different slice of time. They reflect a period when a search engine was an index finger running across the spines of books on a library shelf and the chief mobile communication tool was the cupping of one’s hands. Seldom is there an image of haste. Indeed, most of his subjects appear comfortable in their stillness. Louis T. Moore has left a far greater gift than he knew.

– Susan Taylor Block

I just want to say I love this book. I’ve looked it over a hundred times at the library, while researching the history of Greenfield Lake and every time I look through it I feel like I see something new. Great work!