by Susan Taylor Block

(Click to magnify photos. Double click and scroll to see more.)

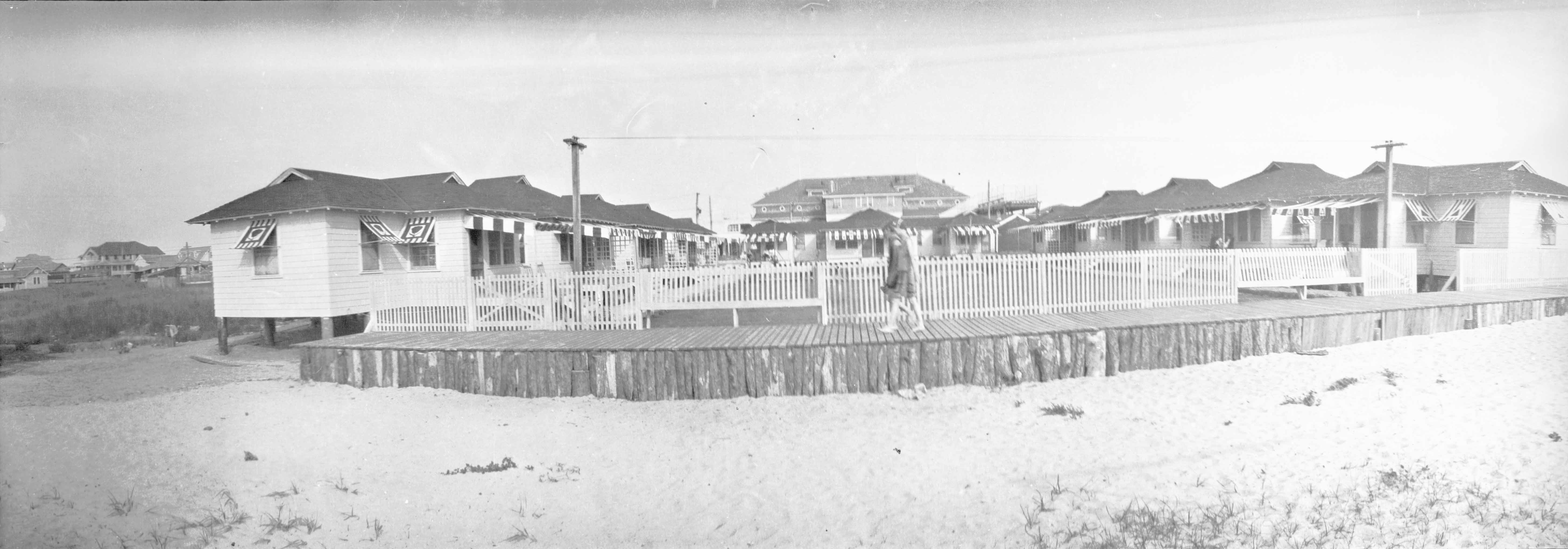

A portion of the photo above was featured on a popular postcard, issued in the late 1920s. Here, the eastern end of the Oceanic can be seen on the left. At one time, Hugh MacRae’s Tide Water Power Company owned the Oceanic, Lumina, the streetcar system, and the Harbor Island Pavilion. The resulting synergy was apparent in shared advertisements, joint discounts, and early recycling: rails left over from the beach car line supported some Oceanic walkways. (964)

This is Harbor Island in 1932. Local agents for A. E. Fitkin, a Florida-based development company working under the name Wilmington-Wrightsville Beach Causeway Company, built the causeway from the intersection of Airlie Road and present-day Eastwood Road, to Wrightsville Beach.

“Thanks to the dredge, Caulkins Territory, an area long sacred to the electric train has been opened to the motor car,” stated the Morning Star. The total bill was $138,000. The thoroughfare opened June 10, 1926. (905)

Harbor Island offered plenty of elbow room in the 1930s. The stucco house on the left belonged to Dr. Fred Wysong of Burgaw. The Harbor Island Pavilion is recognizable by the pyramid shaped roof. John Colucci owned the large two-story house in the center and the house to its right was the famous Villa Margarita. Wilmington Star News publisher Rye Page and Harbor Island developers Oliver T. Wallace and Roger Moore, Louis T. Moore’s brother, built Villa Marguerita in 1931. The architectural firm of Lynch and Foard designed the Spanish villa and W. A. Simon served as general contractor. Local businesses cooperated with the Star News to build the Spanish Mission-style house, with all bills paid “in kind.” The elongated building (with a cupola) on the right is the Seashore Hotel, on Wrightsville Beach, but the wide-angle shot distorts the geography. (350)

This is Live Oak Drive on Harbor Island, about 1926. According to Charles B. Carney and Albert V. Hardy, authors of N. C. Hurricanes, prior to a catastrophic storm in 1856, the beach was said to have been one-half mile wide and covered with live oak trees. Water swept across Wrightsville in 1856, uprooting most of the oaks and sweeping debris onto the mainland. Waves broke one-half mile inland and at an elevation of 30 feet. The remaining live oaks at Wrightsville died within a few days.

Neighboring beaches suffered the same fate: as late as the 1930s, it was dangerous to swim at Carolina Beach at high tide because of the obscured tree stumps. (642)

Just being at the beach was enough for some, but Lumina offered a lot more: silent movies on the strand, swimming, a bathhouse, rental bathing suits, bowling, a small restaurant, and children’s night. It was a place to meet fellow Wilmingtonians as well as visitors from all over the United States. There was even an aquarium large enough to house 50 varieties of fish, including sheepshead, drum, perch and pig head mullet.

Designed by Henry Bonitz, Lumina was built on the site of the 19th-century Mayo House, the first hotel at Wrightsville Beach. Lumina opened in 1905 and, from the get-go, was the social capital of the southeast coast. Victorians were not offended: Lumina was a class act. Dress codes were enforced and badly behaved people were removed swiftly from the premises. In the 1920s, Mrs. Cuthbert Martin supervised manners and bouncer Tuck Savage curbed bullies with a scowl. Lumina maintained strict dress codes: as late as the mid-thirties, men were fined $10 when sighted shirtless.

Dances took place weekly. Wilmington florist Will Rehder provided special lighting effects and floral arrangements. Excellent musicians like the Weidemeyer ensemble and Jelly Leftwich’s Duke University Orchestra performed from the acoustically superior bandshell, contributing much to the ambiance. Many Wilmingtonians still speak of their experiences; in the wondrous pavilion, romantic music and ocean breezes could turn a mood into a lifelong memory.

Lighter moments are not forgotten either. Prohibition turned social drinking into a game of cat and mouse. Patrons hid flasks in the sand under Lumina. Some who could not find a flask brought Mason jars. Wrightsville Beach teenagers raided the jars one night, substituting tea for bourbon. They waited in the shadows and watched gleefully as well-dressed gentleman spewed and cursed.

In 2000, Catherine Meier Cameron remembered a Lumina dance in 1933. She was fifteen, and danced the night away with a charming college boy named Bobby Ruark. “I can still remember what he was wearing,” she added, “a tweed jacket with suede patches on the elbows and tan trousers.” Robert Ruark became a famous novelist, peppering his work with characters that bear strong resemblance to Wilmingtonians he once knew. (374)

“Here many Beach visitors who do not care for dancing enjoy the latest cinema attractions, all the while being entertained by the music from the dance floor borne gently to them on the cool evening breeze,” stated Louis T. Moore in a 1929 Wrightsville Beach brochure. Before “talkies” rendered it obsolete, children enjoyed Lumina’s unconventional theater, too. One night a week, all youngsters who measured 51 inches tall or less were admitted free, not only for movies, but also for dancing, games, and plays. During the early twenties, Lumina occasionally offered free nights to Confederate veterans, a relatively small sacrifice by that time. (342)

“Little ideal homes for the summer,” read the real estate ads. Shore Acres, Oliver T. Wallace’s development company, built Pomando Walk, in 1924. The complex was named for a city in Florida, but the spelling evolved through the years to match the mispronunciation: Pomander. Designed by architect James Borden Lynch to blend with its dominant neighbor, Lumina Pavilion, Pomando consisted of 16 three-room apartments and 4 four-room apartments, all surrounding a carefully manicured quadrangle. The units rented by the month: $20 in June 1932, which included gas, water and electricity. A small trap door at the rear of each unit kept garbage out of sight until sanitation workers paid a call.

In the early 1930s, Thomas Appleberry spent childhood summers at Pomando Walk. He remembered those trap doors, just big enough to create a secret exit for a little boy, and the delights of living at Wrightsville Beach. David Brinkley, an older boy who also lived at Pomando Walk in the 1930s and who played board games at the Appleberrys’ apartment, grew up to become one of America’s most well-known newsmen.

Pomando Walk changed hands from Wallace’s Shore Acres Development to Tide Water Power and Light to P. R. Smith and C. B. Parmele and then, simply to P. R. Smith. Mr. Smith’s wife, Bess, refurbished Pomando Walk before World War II. When war began, the U. S. Government leased the units from the Smiths for military personnel. In 1954, Hurricane Hazel destoyed James Lynch’s creation, but the land was redeveloped. (343)

Here, Julius Herbst lets his son, Robert T. Herbst, hold the wheel while Mr. Moore takes a series of photos for a 1929 brochure, “Wrightsville Beach, a real ocean resort near Wilmington, N. C.”

“Herbst Boat Works and its Julius Herbst, racers of the lion’s share of winning outboard motor boats during the past several seasons, including the National Championship races on the Cape Fear River last October and the New York-Albany marathon this Spring,” read Mr. Moore’s text. Julius Herbst also crafted a landlocked work: the altar at Lebanon Chapel, in Airlie Gardens. (272)

“Even the dogs like the surf at Wrightsville Beach,” wrote spinner Louis T. Moore. The Scottie pictured belonged to his daughter, Peggy, but a beachcomber was just as likely to see a horse swimming in those days.

According to Luther T. Rogers, Jr., his father used horses to help clear sites at Wrightsville Beach. Harnessed to large rope-laced scoops, they hauled earth from one location to another. One of the horses loved to cool off with a swim in the surf.

July 11, 1926 was a sad day for the “hundreds who have enjoyed watching that handsome grey horse belonging to Luther T. Rogers, contractor, as she took her daily dip in the great, green sea.”

The horse swam too far that day and became so fatigued she couldn’t make it back to shore. Lifeguards immediately launched a rescue boat, but were too late to save “the old grey mare.” She did however rate a two-column obituary in the Morning Star the following day. (871)

The federal dredge Henry Bacon, was named in honor of Henry Bacon, Sr., the civil engineer who masterminded “The Rocks” at Fort Fisher. The dredge helped transform New Hanover County tidal marshes into links in the Intracoastal Waterway chain. The project took five years, from 1927 to 1932. The Henry Bacon, built in 1930, dredged the channel, then continued to maintain it.

“Somehow we can’t get used to seeing boats chugging merrily along the Wrightsville Sound section,” wrote one Wilmington watcher, about 1933. “We remember the days when we pushed a flat-bottomed boat over that same route with barely enough water under the keel to float our noble craft. And then yesterday, our eyes popped even wider to view the dredge Henry Bacon wagging sluggishly along the waterway in search of stray mud bumps.”

During World War II, after being converted from coal to oil, the Henry Bacon dredged channels and harbors in Hawaii and Okinawa. After a stay in Savannah, it was called into Air Force service in Newfoundland, in 1952.

Henry Bacon, Sr. was also honored in the naming of the liberty ship Henry Bacon, christened November 11, 1942. The 40th ship launched in Wilmington during World War II, it was sunk off Norway by German air power in April 1945. (759)

Copyright: Susan Taylor Block (Text) and New Hanover County Public Library (Photos)

I loved reading this article and seeing the pictures. I was born at James Walker Nemorial Hospital in 1921 and lived in Wilmington until 1947. Beulah Meier was my aunt and I lived with her family when I was in my early teens. My cousin, Katherine, (known to me as Tina) and I went to Lumina every night and danced, danced, danced. This was the time of the Little Apple and then the Big Apple. We never danced with anyone more than a couple of minutes and then someone would “cut in.” I can remember dancing with Shooney (think that’s right) Brittain who was so good at the “jitterbug” everyone wanted to dance with him. No dances on Sunday but there was always a concert by the orchestra booked for that summer. We were there, of course, and would find a corner in which to dance until a staff member would find us and make us stop. Sunday dancing was considered a sin! I remember the Jelly Leftwich orchestra but also “Dean Hudson and his Men of Renown.” Those were glorious times.

We were living there and participating in all the fun even before the street cars came all the way to Lumina (Station 7). I can’t remember but I assume when the street cars (which departed from Front and Princess) arrived at Harbor Island we were transferred to something else which crossed the bridge and went all the way to Lumina with stops along the way, of course.

It was a glorious time and the Meier family was involved in Wrightsville from the very early days. Beulah was one of my father’s sisters. Don’t know how many people were aware she came from a very large but poor family who lived on a farm close to Mt. Olive. She was a very talented and determined person who succeeded at everything she undertook. The word “self-made” was, I think coined to describe her.

Such memories I have.