by Susan Taylor Block

(Click on photos to magnify them. Double-click and scroll to see more.)

The Dram Tree (center), once located just south of Sunset Park, drew its name from the tradition of sailors taking a dram of rum there, either to celebrate their passage through the tricky shoals of Cape Fear or to steady their nerves as they headed for open seas. The tree became a political boundary in Colonial days when, during the rivalry between Newton (later Wilmington) and Brunswick Town, Newton boatmen refused to carry produce any closer to Brunswick than the Dram Tree. It was used as a buoy during nineteenth-century sailing races and, in 1909, the tree was a star attraction when President William Howard Taft visited Wilmington.

For fear construction workers would harm it, there was public outcry in 1918 when the Carolina Shipyard was built near the Dram Tree. Shipyard officials went to great pains to preserve it, but many less famous ones were felled. In 1929, Louis T. Moore said the Dram Tree “now stands well into the river, 50-75 feet from its companions.” Sadly, a workman who knew no better destroyed the tree in the 1940s. A gavel belonging to Wilmington’s Cape Fear Garden Club, carved from a Dram Tree branch, is all that remains. (1002)

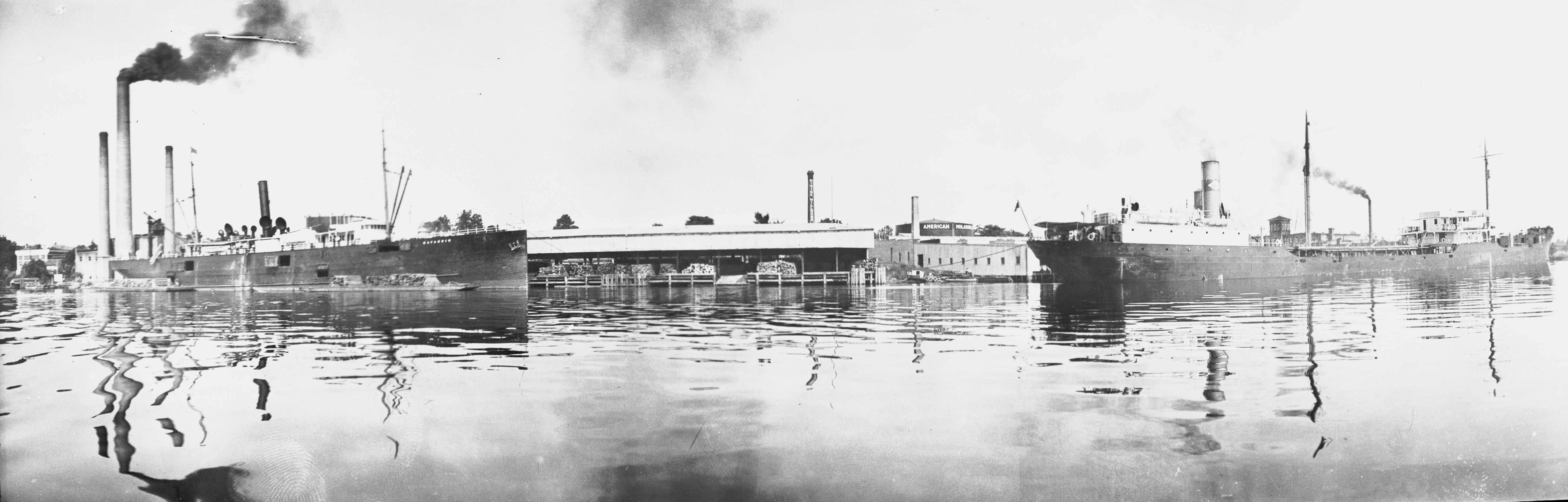

Here, the tanker on the right is unloading a million gallons of molasses. The wharf in the center belonged to the Clyde Line Shipping Company, part of the harbor scene as early as 1869. If the dock still existed, it would be located under the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge. In the 1920s, agent M. W. Riley headed the company of 150 employees. This photo was published in the Morning Star and in a book titled Wilmington Citizens. Louis T. Moore contributed general historical information for the book, a series of biographical sketches written by R. H. Fisher. (463)

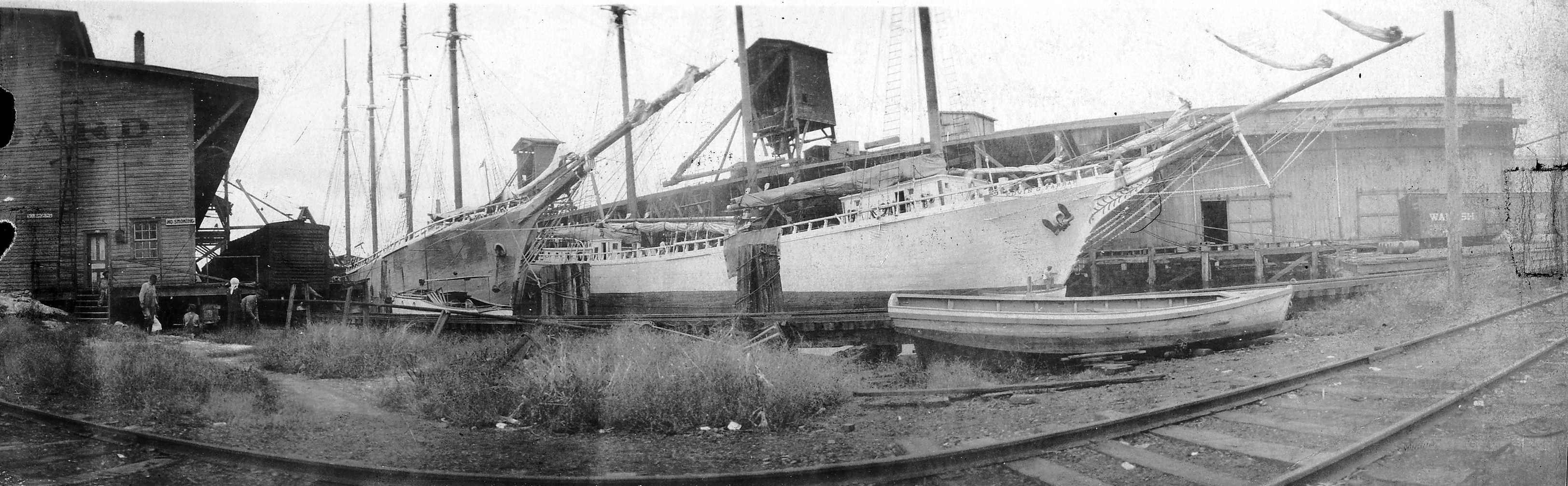

In the early 1920s, ships ran aground routinely on the Cape Fear River. Louis T. Moore campaigned fervently to deepen the channel into Wilmington from 26 to at least 30 feet. In April 1927, Moore and a delegation representing the Chamber of Commerce, the Wilmington Traffic Association and river pilots traveled to Washington, D. C. to appear before the U. S. Rivers and Harbors Commission. Subsequently, the federal government spent a million dollars to deepen the Cape Fear River from its mouth to Wilmington. When the project was completed, ships with a 32-foot draft could navigate the channel successfully. Here, a schooner loads at the Wilmington Terminal Warehouse Company. (963)

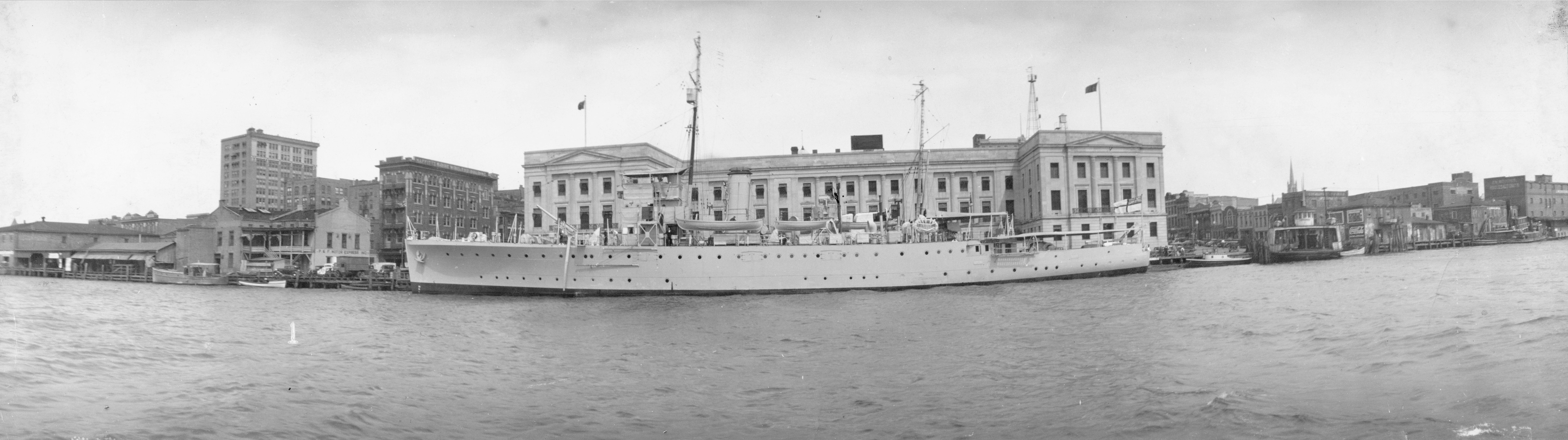

In 1935, the British warship Scarborough visited Wilmington under the command of O. W. Cornwallis, a descendant of British General Lord Charles Cornwallis. During the American Revolution, General Cornwallis occupied the Burgwin-Wright House, April 7 through 21, 1781. Unlike his predecessor, O. W. Cornwallis was given a warm welcome and his short stay was considered a “Good Will Visit.”

The slender five-story building at the foot of Princess Street was owned by maritime force Clarence Dudley Maffitt (1873-1958), oldest son of Civil War blockade runner Captain John Newland Maffitt. In 1902, C. D. Maffitt’s yachting agency was sanctioned as a “Rudder Station,” one of 125 locations worldwide to win the approval of The Rudder, “the official yachting magazine of America.”

In addition to boat brokering and shipping management, Maffitt employed three expert sailmakers who also created line, hammocks and awnings. The top floor of his building was occupied by the U. S. Naval Radio Station, an operation managed by Fred Hanek. (940)

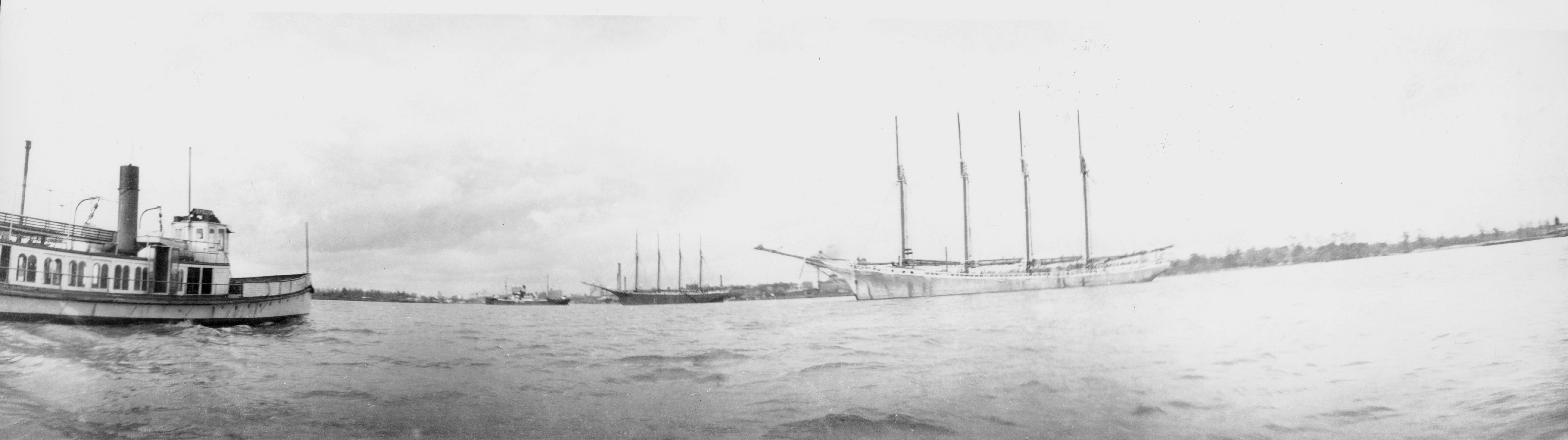

According to Louis T. Moore, the Cape Fear River once was “a veritable forest of masts.” The schooners pictured here are the Edward R. Smith and the Nomis, but tall ships would soon become rare sights on the river. Their allure has never been matched.

The vessel on the left it the steamer Evelyn that replaced the beloved steamer Wilmington, in 1925. Both riverboats traveled regularly from Wilmington to Southport, with stops along the way. According to N. C. state archeologist Nathan Henry, the Evelyn, built in 1892 at City Island, New York, had a steel hull and mahogany upper works. She was used as a private yacht for many years, then converted to diesel power in Wilmington, becoming the first “full” diesel powered vessel operating on the Cape Fear. Sadly, the Evelyn burned in 1926. (819)

Thirty miles of unbroken tree-studded shoreline can be enjoyed from a big, high-backed easy rocker on the breeze-swept upper deck,” stated on ebullient Morning Star writer, about 1918, of the steamer Wilmington. Captain John W. Harper’s flagship first entered the Cape Fear River in 1891. It had an iron propeller, was 130 feet long, and on a good day could reach a speed of 16 miles an hour. The Wilmington, equipped to carry 511 passengers, made stops on request, but docked routinely at Orton Plantation, Southport, and Carolina Beach.

Groups from both white and black Sunday schools frequently rented the steamer for annual picnics. Dr. Robert M. Fales (1907-1995) rode aboard the Wilmington when members of First Baptist Church made their semi-annual trek to Carolina Beach, visiting Wrightsville Beach on alternate years. “Other than Chirstmas Day, most children in town considered the Sunday School excursion the best day of the year,” said Dr. Fales. “The Wilmington was a swift vessel and had practically no vibration,” he said.

On July 5, 1926, 500 members of St. Stephen’s A. M. E. Church boarded the Wilmington for an excursion to Southport. Church members, led by T. H. Hooper, were officially welcomed and “shown every kindness by the Mayor C. L. Stevens and citizenry.” Excursions of this sort and regular passenger traffic changed when automobiles proliferated. The City of Wilmington was too large to support itself financially and was sold. (767)

Captain L. D. Potter, owner of a large and powerful tugboat christened The O’Brien Girls, purchased a smaller steamer, Isleboro, and renamed it City of Southport. It left Wilmington every day at 10 a.m. and departed Southport at 4 p.m. It was a successful venture for several years.

Known as “Courtesy” for his impeccable manners, Captain Potter (seated atop walkway) was a sort of human gazetteer, providing information on the naming and location of many local sites to anyone who asked. Guests were accustomed to listening to piano music while they cruised the Cape Fear, but in 1930, Captain Potter added the new tones of a Victrola. (768)

The Sachem II, a 78’ yacht owned by Clarence Hooker of New Haven, was a frequent sight along the Wilmington waterfront. C. D. Maffitt was agent for Sachem II and many other yachts. Maffitt himself owned a small fleet of boats through the years, including Hart Saver, Miranda, Carolyn, Anna, The Smart Set, and Scuppernong. In 1910, Maffitt was jubilant that he navigated his launch The Smart Set from Wrightsville Beach to the foot of Princess Street in just seven hours. (237)

This photograph was taken just east of the Cape Fear River, about 1925, at Hilton Lumber Company, not far from the spot where Cornelius Harnett’s colonlal home, “Maynard,” once stood. Smith Creek, pictured here in relatively pristine condition, was still a popular recreational destination in those days. A 1907 account of a voyage aboard Maffitt’s launch, Scuppernong, appeared in the Wilmington Dispatch, and is assumed to have been written by Dispatch reporter Louis T. Moore.

“Another delightful boating party transpired this week, given by C. D. Maffitt complimentary to Miss Fannie Murchison and friends. Up the Cape Fear to just above Angola went the trim little craft, then up Smith’s Creek for 7 or 8 miles. Aboard the boat refreshments were served and music rendered by a Victor talking machine which presented records of Melba, Patti, Caruso and others.

“The party was made up of Misses Agnes McQueen, Alice Boatwright, Mary Calder, Bessie Loder, Jennie Murchison, Annette Munds, Miss Holmes and Miss Smallbones, Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Empie, and Messrs. Graham Kenan, Milton Calder, Swift Boatwright and C. D. Maffitt.” (295)

This standard size photograph was taken March 1, 1912 by Louis T. Moore. At that time, the ferry system was owned by Oscar Durant in Wilmington, but an African American family, the Joneses of Brunswick County, operated it. The man standing near the stern is William Jones, a veteran ferryman. The passengers are probably Brunswick County farmers who regularly took the ferry on Friday, bringing their wares to Wilmington for the Saturday market. They returned on Saturday afternoon.

Bill Jones ran the ferry system when it was little more than a rowboat. Three or four passengers per trip paid five cents apiece to Mr. Durant, who kept the coins in a pouch he called a “shotsack.” Bill Jones, a tall, powerfully built man, worked the oars from one side of the river to the other, and back again. He also collected fees in Mr. Durant’s absence.

After 1900, the flat pictured here replaced the little rowboat. The May, a gas launch that propelled the flat across the river and warped it onto the landing, was added in 1906 after much refurbishment.

Forces of nature made the job difficult. In 1908, heavy flooding left 2 to 5 feet of water on Eagles Island, the ferry equipment had to be tied to trees until the turbulent waters subsided. A horse jumped overboard one rough day, pulling a buggy with him. And once, a whole carload of people met their death when their vehicle slipped back into troubled water at the Wilmington dock. Divers retrieved the bodies and, just hours later, a small crane lifted the automobile out of the water. The car’s lights were still burning, a fact used later in a battery advertisement.

Bill Jones, his son Abraham, and his young grandson Clarence all worked on the ferry. They were the last Cape Fear residents to carry on a proud old tradition. Travel writer Edward King visited Wilmington about 1875 and mentioned the good-natured “gondoliers” on the “wide and noble stream.” Prior to the American Revolution, Brunswick Town resident William Dry operated ferries on both sides of Eagles Island. Back then, transportation schedules were even more unreliable. The N. C. General Assembly took pity on passengers and ordered ferry operators to “maintain taverns so that travelers might refresh themselves as they waited.”

William Dry, John Allan Taylor and, later, D. L. Gore owned the service before Oscar Durant purchased it. When larger ferryboats put the gasoline launches out of business, young Clarence Jones (born 1908) went to Orton Plantation, a few miles from the Joneses Brunswick County farm, and asked for a job. He became a legendary gardener, receiving both local honors and national attention. (914)

The ferry John Knox (on right) was named for a chairman of the Brunswick County Commissioners, not the fiery Scottish clergyman. Built in Morehead City in 1919, it cost $43,000. This photograph was taken in 1935, when H M S Scarborough visited Wilmington. (see 940) Another ferry, the Menantic was purchased used, in New York, for $22,000 and arrived in Wilmington, May 2, 1924. In 1929, their last year of operation, the ferries’ service receipts totalled $93,000, based on charges of 84 cents per round trip.

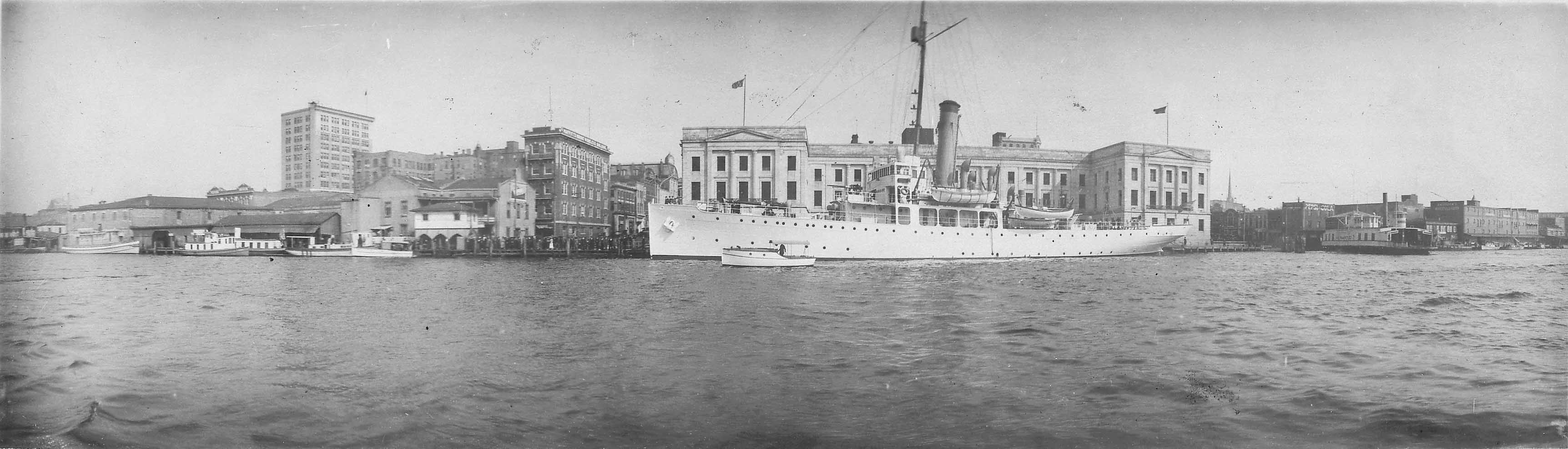

Here, the Murchison Building (left) and Atlantic Trust Building (right), Wilmington’s tallest structures at the time, appear like bookends to the U. S. Custom House. It’s a beautifully composed picture, full of textures and wordless history. (839)

In this view, Point Peter is on the left and Eagles Island, on the right. The 800-acre tract directly across the river from downtown Wilmington is named for Richard Eagles who acquired the property in the 1730s. Louis T. Moore, a stickler for historical accuracy, read seven newspapers a day. In the 1950s, he noticed the local paper was habitually omitting the “s” in Eagles Island. He wrote the editor, his good friend Al Dickson, requesting that he “cease and desist from trying to change an historical name which has stood the test of time for about 225 years” and suggested his reporters be forced to write it a hundred times on the blackboard of the local news room.

Louis Moore’s grandfather and uncle, Benjamin and W. L. Beery, owned Beery Shipyard on Eagles Island. The night Fort Fisher fell, January 15, 1865, the Berrys burned their shipyard rather than have it destroyed by General Terry and his Union soldiers. After the fire, all that was left of the Eagles Island enterprise was a tall brick chimney. Vines soon covered the chimney and it became a conversation piece for Wilmingtonians gazing across at the island.

One day, about 1920, locals noticed the green vines suddenly had shriveled and turned brown. One night, a group of men paid a surprise visit on the old site and discovered an enterprising bootlegger using the old chimney as a giant exhaust pipe for his “blind tiger still.” The moonshiner fled and the chimney soon was covered in greenery again. It remained an Eagles Island landmark until a storm toppled it, a few years later. (123)

Seaboard Air Line facilities, pictured here in 1935, included five large warehouses that had a combined capacity to store 200,000 feet of goods, and their wharves could accommodate six oceangoing steamers. Seaboard owned the only deepwater slips in Wilmington. Water depth and electric winches allowed them to unload 10,000 tons of scrap iron per ship. Their passenger trains gave Wilmingtonians access to points west of the city like Charlotte that were not served by the south-north rails of the Atlantic Coast Line.

The Seaboard office building was the unlikely meeting spot of Thomas A. Edison and Count Guglielmo Marconi in 1899. They conducted wireless experiments and sent a message from one room of the building to another. Both men stayed at The Orton hotel. (258)

The Coast Guard cutter Seminole (1899-1934) preceded the Modoc in Wilmington. Her most famous guest was President William Howard Taft, one of five presidents who visited Wilmington, the others being Washington, Monroe, Filmore and Polk. James Sprunt orchestrated the 4-hour cruise for President Taft, November 9, 1909, and his trusted employee, Lincoln Hill, waited on the president. However, efforts to regale the chief executive aboard the Seminole were thwarted that afternoon “when President Taft succumbed to the influence of a fine day on a quiet river, and calmly went to sleep.”

On July 31, 1919, the Seminole hosted Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy, during the christening of the Cape Fear, a reinforced concrete ship built in Wilmington. Sec. Daniels watched from the Seminole deck as Liberty Shipyard employees launched the ship sideways. It hit the water hard and listed far to one side and then the other, creating walls of water that soaked hundreds of spectators. Small boats were washed up on shore and some of their passengers had to be plucked from the water.

During prohibition, the Seminole went on many liquor patrols, including one off the coast of New England that turned violent.

(Seminole photo courtesy of the Historical Society of the Lower Cape Fear.)

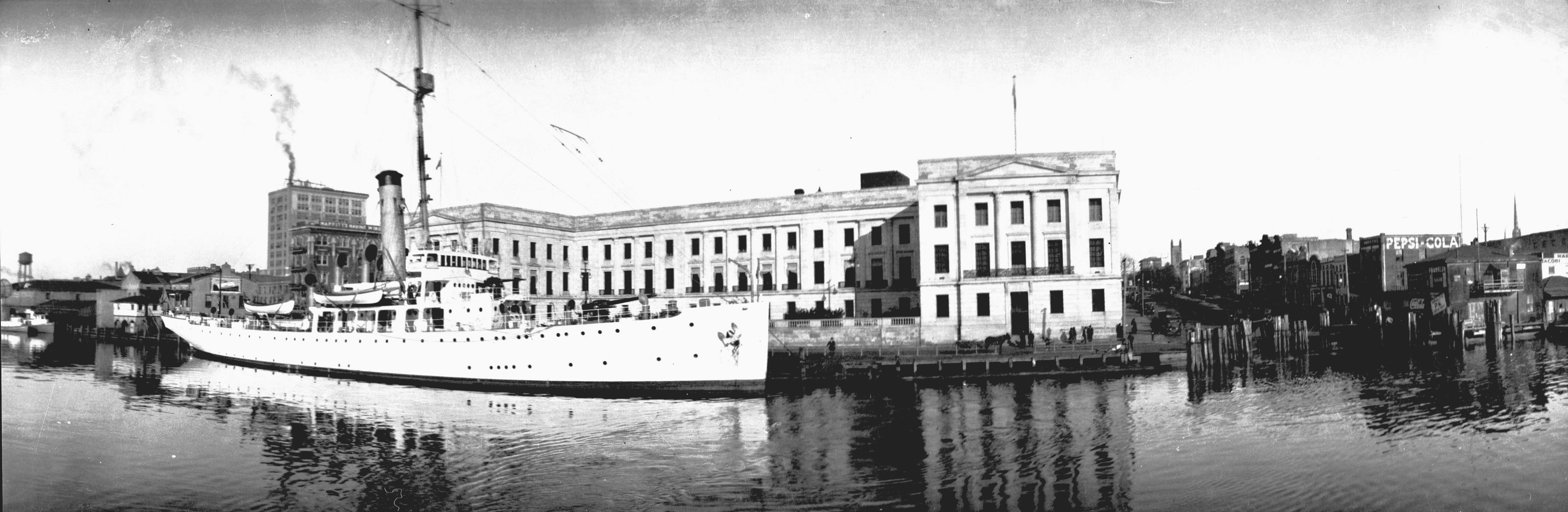

The Coast Guard assigned the Cutter Modoc to Wilmington on September 4, 1922. Like other Wilmington-based cutters, and its primary purpose was to locate and track icebergs. Eventually, tracking rumrunners would lead to more headlines for the Modoc, but prohibition enforcement never affected the serious business of iceberg monitoring. This photograph was one of Louis T. Moore’s favorites. In addition to use as a postcard, the image was superimposed on Chamber of Commerce stationary. (110)

In 1909, when prohibition was enforced, sixty local saloons disappeared but alcohol didn’t. The U. S. Coast Guard rumrunners made only a dent, but publicity magnified their victories. On January 6, 1933, longshoremen spent three hours toting 600 cases of “famed and choice brands” of confiscated liquor from a second-story room in the Custom House to the wharf below. Mrs. Fannie Faison, assistant Collector of the Port, and Coast Guardsmen from the Modoc supervised as bottles were axed and the liquor seeped towards the river. Prohibitionists looked stern and some drinkers looked sad, but many a resourceful Wilmingtonian knew a place on Market Street where some money and a secret car horn code could elicit a jug of moonshine. (210)

Here, the Coast Guard Cutters Modoc and McAdoo dock at Wilmington, while the plodding ferryboat, Menantic, plies the waters. For many years, the houseboat in the foreground was home to an African American man. The McAdoo was named for William G. McAdoo, Secretary of the Treasury in Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet, a cozy position considering he was also married to Eleanor, one of Wilson’s daughters. President Wilson also appointed William McAdoo director general of railroads during World War I. In this capacity, he visited Wilmington in 1918, and socialized with his in-law’s old friends from the days when the President’s father served as minister of First Presbyterian Church.

The 1916 Custom House, on the right, was beautiful and grand beyond proportion for a city Wilmington’s size. President Woodrow Wilson was looking out for old friends in Wilmington. B. F. Keith, Collector of Customs, spearheaded the project. His successor, Colonel Walker Taylor, completed it. The Custom House became the repository of a precious article in 1922 when Archibald Henderson and Gabriella deRosset Waddell donated the city’s invitation to George Washington and the first president’s reply. Washington visited Wilmington in 1791. (233)

In the 1920s, Wilmington’s two largest businesses were the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and Alexander Sprunt and Son. The Sprunt’s local operation, Champion Compress, occupied waterfront property, with docks, room for five compresses and a vast warehouse. On a typical day in 1923, the main warehouse held 136,000 bales of cotton, 90,000 pounds of nitrate and 50,000 pounds of cement. Often, sugar was also stored in the warehouse. In fact, the space was so large that certain prized hunting dogs from Pinehurst used to visit for months at a time, running the length of the building to stay in shape for “the season.”

Until his death, in 1924, James Sprunt was chief executive of Alexander Sprunt and Son, a major international cotton exporter. According to Sprunt’s step-grandson, Peter Browne Ruffin, Mr. Sprunt oversaw operations around the world. “He was the main cog in Alexander Sprunt and Son and he went to Europe many times promoting his business,” said Mr. Ruffin. “Alexander Sprunt and Son had offices in Europe and a number of Wilmington men were running them, including Mr. Devereux Lippitt in Bremen and Mr. Rob James in Rotterdam; a Messers Louis Orrell and Tom Orrell had an office in LeHavre. Also, there was an office in Liverpool, but that was headed by a man from Scotland.” (811)

Here, longshoremen unload sugar at Champion Compress wharf. James Sprunt was well-known for his generosity to his African American employees. One who remembered him in 1999 was F. Clarence Jones of Brunswick County. Mr. Jones worked briefly for James Sprunt before he died in 1924, but members of the Jones family had worked for the Sprunts on the Wilmington wharves and at Orton Plantation for many years.

“Mr. Sprunt always would provide things for the black people. You know they were poor as snakes back then. With Christmas coming, he would send his workmen to fruit stands, grocery stores and other places to buy up just tons of all kinds of things: meat, lard, flour, rice. And he’d have a barrel and he’d pack those barrels with what they bought, just as long as he could fit something else in it. Ham was a big thing. He put a ham in every barrel, then he’d put fruit on top and cover it over with burlap and put a hoop on it. Then all of his employees would have a barrel.

“The steamer Wilmington would come down and bring the barrels (to the Brunswick County employees) to Orton dock. John Ed Pearsall was the (Orton) foreman at the time. He’d go down and meet the boat and get the freight. He would take care of all the transportation from the wharf to the Orton office. Everybody would come down at Chritsmas to get a barrel. They had to bring their wagons, carts, oxen or horses, them that had horses, and load the barrels and go home. Well they had enough in those barrels to last almost until Spring. And Mr. James did that every year and when he died, his son, Mr. Laurence, did it.” (251)

This photograph, taken from the roof of the Murchison Building, shows the depth of the Champion Compress buildings (on right.) During Wilmington’s 1898 riot, the Sprunt business complex became a haven for African Americans. Clarence Jones’s uncle was one of them. Mr. Jones heard him tell the story many times and retold it in 1999.

“The riot was moving down the street, moving east to west. Well, the black people were just about to the end of the journey. They couldn’t go further than the river. So Mr. James opened the compress, the warehouse doors, and they all rushed in. He wrapped up in a United States flag. It was one of these great big flags and he wrapped it around himself and went out and stood at the door and said, ‘Now shoot this flag and then you can come in.’

“He saved many people. He protected them. I’ve been knowing the Sprunts ever since I knew Mr. James. He was a good-hearted person. And then the boys came right along behind him: his son, Mr. Laurence, and his grandsons.” (92)

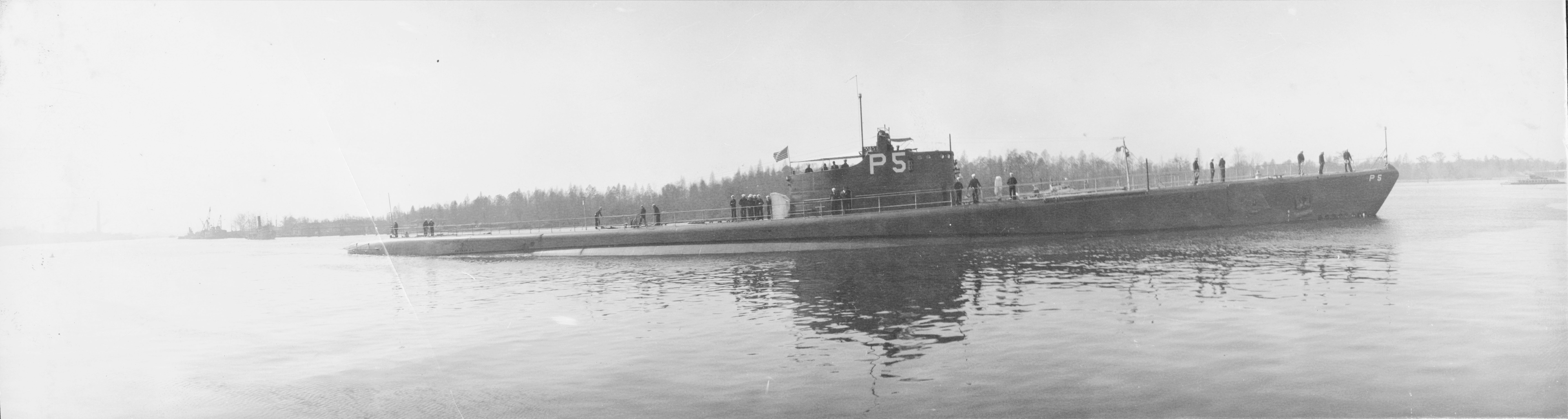

On her shakedown cruise, theUSS Perch arrived at Southport, January 14, 1937, for a two-day visit. She was accompanied by the tug Blanche and piloted through the fearful cape by Captain H. St. George. Lieut. Commander G. C. Crawford was greeted at the dock by Wilmington mayor Walter H. Blair, W. H. Sprunt, Lieut. J. J. Hutson, representative of the Modoc, and Louis T. Moore.

On January 16, the Perch docked at the Champion Compress wharf in Wilmington where she remained for three days. The crew’s first two meals must have been a welcome break from submarine fare. The first stop was the Hotel Cape Fear for a luncheon hosted by Wilmington’s four civic clubs. Dinner that evening was an oyster roast at Harrill’s-on-the-Sound, off Greenville Loop Road.

Louis T. Moore was busy for weeks prior to the sub’s visit, entreating collectors to bring blank covers to the Chamber of Commerce. He took over 500 envelopes aboard on January 16 for commemorative cancellation. “Affixing of the cachets is being handled by the Chamber of Commerce with the cooperation of the Cape Fear Stamp and Cover club,” Moore announced.

Today, the Perch lies 190 feet beneath the surface of the Java Sea. During World War II, the submarine was part of the Pacific fleet. In March 1942, the 59-man crew was forced to abandon ship after it was damaged in battles with the Japanese Imperial Navy. The Japanese placed the entire crew in POW camps. Six of the Americans died, and 53 survived.

Mr. Moore shot this photo on a cloudy day, but the exhaust towers of Tidewater Power, situated at the foot of Castle Street, are visible still through the mist. (822)

The smokestacks of Tidewater Power Company dominate the scene at the foot of Castle Street. Tidewater Power was incorporated in 1907 when Hugh MacRae consolidated Wilmington Gas Light, Wilmington Street Railway and Wilmington Seaboard Railway companies. By the 1920s, the company owned and operated the local streetcar system and sold gas and power to 75 cities and towns.

In 1924, Tidewater Power Company added a new 200-foot smokestack to the plant at the foot of Castle Street. The commercial improvement became the talk of the town when construction workers discovered remains of a ship, submerged near the shore. More than fifty people came forward to identify it, each with a story.

On close examination, the sunken vessel proved to be older than any of the stories. It had knees made from tree roots and nails that were hand-forged copper spikes. (Double click and scan left to view the neighborhood, north to Nun Street.) (289)

Herbst Boat Works, located just west of the intersection of Southern and Burnett boulevards in Sunset Park, made powerboats like the one seen here. Housed in a large frame building that housed a part of the World War I enterprise, Liberty Shipyard, Herbst Boat Works was a popular hangout for area boaters, including Joe Willard Whitted. “The powerboats were outboards, one-step hydroplanes,” said Whitted. “There was a 2-inch radius in the hull, and when they were going their fastest, there was practically nothing left in the water but the motor.”

Julius Herbst, a talented woodwright, crafted the boats, but his elderly father, Frank Herbst, was the center of attention. The first person to patent an inboard/outboard motor, a homing pigeon expert, former manager of Lumina pavilion, and an early automobile dealer — he had lots to talk about. A musician, too, he owned a violin that was over 250 years old. He liked to play it while his son and his employees went about the rough and dusty business of boat construction. At age 102, Frank Herbst, who thrived on a diet of oatmeal, decided he had lived long enough. He refused his porridge and died a few days later.

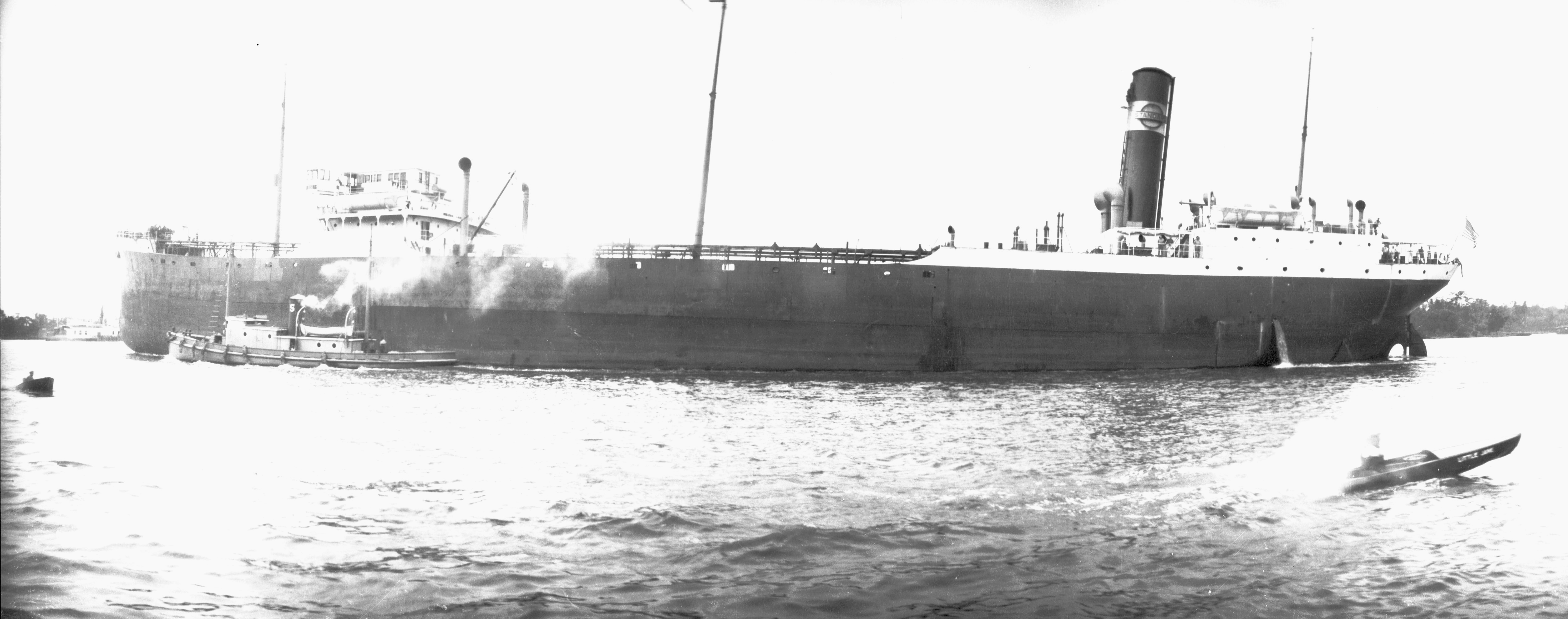

Here, a member of Wilmington’s Frying Pan Power Boat Club scoots about while a Standard Oil Tanker and accompanying tug plod through the waters of the Cape Fear. Louis T. Moore wrote that the club “is doing much to develop the sport of motor boating. The extension of the Intra-Coastal Canal from Beaufort to Wilmington, that has been started, will greatly increase the volume of yachting and boating at Wilmington and its resorts.” (240)

Copyright: Susan Taylor Block (Text) and New Hanover County Public Library (Photos)

The Steamer WILMINGTON was sold in 1926 to the Bee Line Ferry Company. She ran as the WILMINGTON for a few years, and then in 1930 she was renovated and switched from being a steam vessel to a diesel vessel. At that time her name was changed to the PINELLAS. She ran between Pinellas Point in St. Petersburg, FL and Piney Point (Palmetto, FL) across Tampa Bay. During WWII the US Navy commandeered the Bee Line ferries. The PINELLAS had her name changed to the SEABROOK (YFB-38) and she ran between the Naval Air Station and Jacksonville, FL. Both Joe and David Winters had captained ferries for the Bee Line Company, but they moved with their families to Jacksonville and ran the boats for the Navy. After the War, the vessels were sold back to the Bee Line Ferry Company and ran until September 1954 when the first Sunshine Skyway Bridge was completed across Tampa Bay. Capt. Joe Winters then purchased the old ferry and renamed her the MISS PINELLAS and ran her for fishing and other excursions under the name Tampa Bay Excursions, Inc. The boat was sold in October 1965. The last I currently know of her was that she had been discovered by the US Coast Guard adrift off the coast of Cuba. The current owners had struck a deal to return a group back to Cuba. At the time, Arthur Velasco, an owner, said it was unsure if the MISS PINELLAS would be sent to South America to run on the Amazon River, but he would see.